A Yale-trained historian of ideas specializing in the history of American medicine and psychiatry, Paul E. Stepansky, Ph.D. enjoyed a 30-year career as consulting editor and publisher for leading psychiatrists and psychoanalysts in America. Long sought out by physician-writers seeking high-level help developing book projects, Stepansky has worked collaboratively with senior writers in fields as diverse as psychiatry, medical sociology, psychopharmacology, surgery, and architecture. Within psychiatry and psychoanalysis, Margaret Mahler and Heinz Kohut were among his private clients. From 1983 through 2006, he was Managing Director of The Analytic Press, Inc., which he built into a premier American imprint of mental health books and journals.

Stepansky’s writing career dates back to his undergraduate years at Princeton, when he was hired by University of Pennsylvania psychiatrist Karl Rickels to help write journal articles based on clinical drug trials conducted by Rickels’ psychopharmacology research unit. He shared authorship of several of the unit’s publications on psychotropic drug use in family practice. During this same period, he was hired by Princeton’s Department of Sociology to write critical reviews of books that applied Erik Erikson’s then popular psychosocial theory of development to historical subjects. He graduated from Princeton in 1973 as a university scholar and recipient of the Walter Phelps Hall Prize in European history. At Yale, where he received graduate training in European intellectual history, he was the first Kanzer Foundation Fellow for Psychoanalytic Studies in the Humanities.

Stepansky’s writing career dates back to his undergraduate years at Princeton, when he was hired by University of Pennsylvania psychiatrist Karl Rickels to help write journal articles based on clinical drug trials conducted by Rickels’ psychopharmacology research unit. He shared authorship of several of the unit’s publications on psychotropic drug use in family practice. During this same period, he was hired by Princeton’s Department of Sociology to write critical reviews of books that applied Erik Erikson’s then popular psychosocial theory of development to historical subjects. He graduated from Princeton in 1973 as a university scholar and recipient of the Walter Phelps Hall Prize in European history. At Yale, where he received graduate training in European intellectual history, he was the first Kanzer Foundation Fellow for Psychoanalytic Studies in the Humanities.

Stepansky’s own scholarship has taken him from early articles on the role of psychiatry in family medicine; to history of psychoanalysis (A History of Aggression in Freud [1977]; In Freud’s Shadow: Adler in Context [1983]); to interdisciplinary studies in medicine and psychiatry (Freud, Surgery, and the Surgeons [1999]); to historical critiques of psychiatry and psychoanalysis in relation to scientific medicine as it evolved in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Psychoanalysis at the Margins [2009]).

In 2006, Stepansky stepped down from his position at The Analytic Press to pursue full-time scholarly work in the history and sociology of American medicine. Topics of special interest include the history of psychiatric and medical book and journal publishing in twentieth-century America; the history of primary care medicine in America; the history of medical technologies, old and new; the history of medical education; the interface of psychiatry and medicine in America since World War II; and the professionalization of women in medicine, nursing, and social work in nineteenth- and twentieth-century America. His work on this final topic gained expression in his one-day conference, “The Professionalization of Women in Medicine, Nursing, and Social Work: A Comparative Historical Inquiry,” at University Hospital of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey on March 12, 2013.

Stepansky has taught advanced seminars in history of medicine, including a seminar on “Women, Their Bodies, Their Health, and Their Doctors: America, 1850 to the Present,” at Montclair State University. He retains an appointment at Weill-Cornell Medical College, where he is interdisciplinary research faculty at the DeWitt Wallace Institute of the History of Psychiatry.

In 2010 Stepansky launched Keynote Books to publish and distribute his stirring memoir of his father, William Stepansky, M.D., a remarkable GP of the postwar generation, and other general-interest works in medicine and society. The Last Family Doctor: Remembering My Father’s Medicine (Keynote, 2011) has been praised as a “perfect recapturing of an earlier era in medicine” (Howard Rabinowitz, M.D., Jefferson Medical College) and “a unique and compelling account of mid-twentieth century American medical practice” (Howard Kushner, Ph.D., Emory University). William Stepansky, M.D., indelibly captured in his son’s portrait, has been deemed “the doctor we all deserve” (Daniel Carlat, M.D., The Carlat Psychiatry Report) and, for young physicians, “a model for behavior” (Howard Spiro, M.D., Yale Journal for Humanities in Medicine). Keynote has since published the expanded second edition of David Newman’s Talking with Doctors (Keynote, 2011) and Elaine Siegel’s memoir of her childhood, Chaos Unbound: A Jewish Childhood in Nazi Berlin (Keynote, 2013).

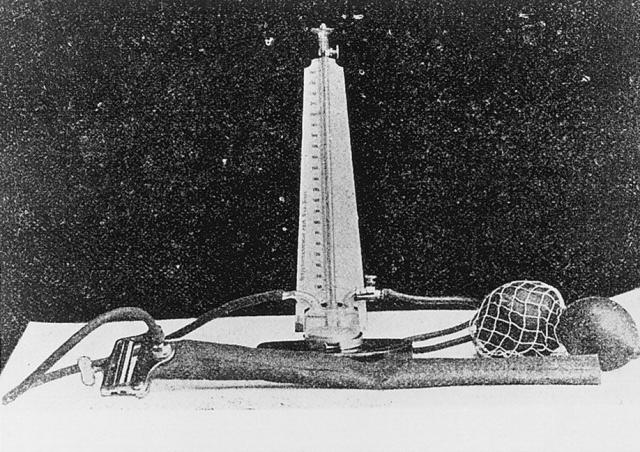

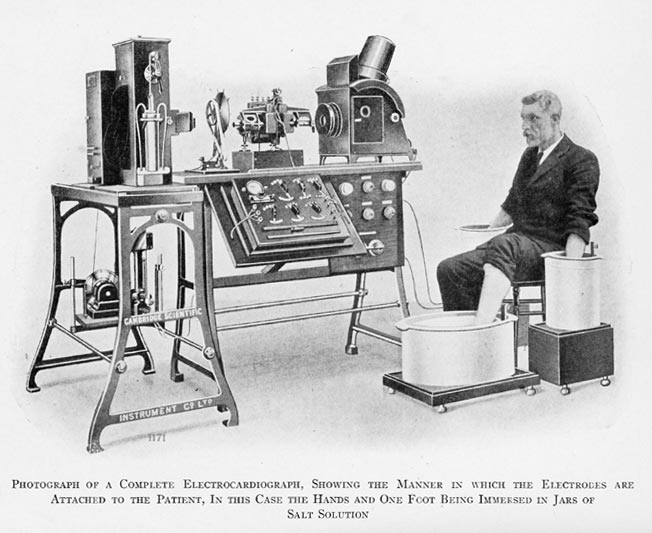

The scholarly outgrowth of Stepansky’s thinking about the history of primary care medicine, especially the evolution of the doctor-patient relationship in relation to procedure, touch, and technology, is In the Hands of Doctors: Touch and Trust in Medical Care, winner of the 2017 Independent Publisher Book Awards Bronze Medal. It has been hailed by the historian Rosemary Stevens as “an engaging, richly documented, brilliant critique of the bond between doctor and patient, ranging from classical times through the present” and “a superb introduction to the role of the doctor in a continuing historical context.”

Broadening his purview on the evolution of primary care in America, Stepansky has written about modern nursing and the origins of the nurse practitioner movement. This focus gains expression in Easing Pain on the Western Front: American Nurses of the Great War and the Birth of Modern Nursing Practice (McFarland, 2020). This examination of nursing care of American, Canadian, and British nurses during World War I has been lauded as “an historically informed examination of nurses’ actual wartime practices that changed the experience of wounded soldiers, in no small measure through nurses’ skilled use of cutting-edge technologies that contributed to the transformation of American nursing in the decades following the Great War.” (Patricia D’Antonio). Reviewing the book in Medical Humanities, Richard Prior deemed it “a unique book that rightfully takes a prominent place among the scholarly histories of healthcare during the Great War.”

Thanks for this blog–a necessary remedy! Medical students are swamped by over-specialized fragments of knowledge, becoming experts on fractions and forgetting whole numbers. Even more surprising is the ignorance of so many psychoanalysts and psychotherapists about the history of their concepts.

Came here via the intro on the CMH blog and loving it! Would love to read and learn more in the days to come. Maybe indulge in my fascination with the history of medicine as well! Thanks for writing such an impeccably researched blog.

Many thanks. I’ll do my best to keep you coming back.

Five years on… and I am still coming back. Just noticed my previous comment here and thought of letting you know that I have been hooked to your blog for a while now!

Pingback: Medicine, Health, and History: Introducing a new medical humanities blog by Paul E. Stepansky | Centre for Medical Humanities