DEMOCRACY

Out with the Trash

Rene Laennec's wooden-tube, monaural stethoscope of 1816

James Mackenzie’s clinical polygraph of 1892 (show here in a refined version of 1914) permitted simultaneous tracings, via separate receivers, of the radial, venous, and arterial pulses. Used in conjunction with an even lower-tech instrument, the stethoscope, it allowed Mackenzie to make the first diagnosis of “auricular paralysis,” i.e., atrial fibrillation, in 1898.

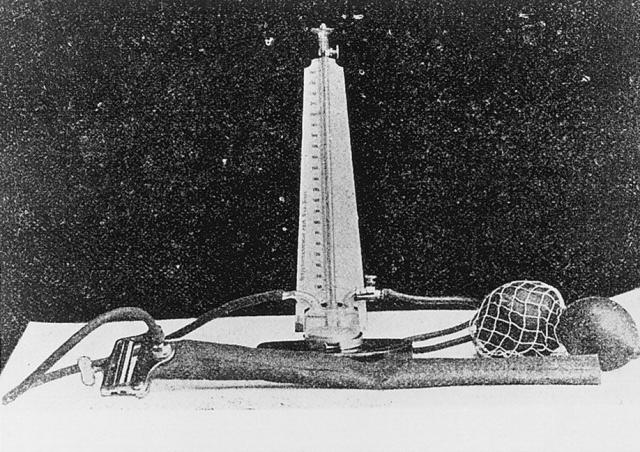

Scipione Riva-Rocci's mercury sphygmomanometer of 1896, little different from mercury-column blood pressure meters of today

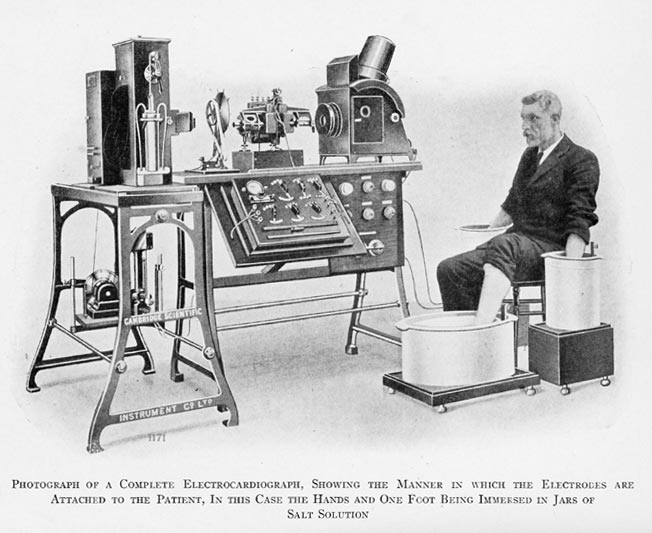

The string-galvanometer EKG machine developed by Willem Einthoven between 1900 and 1903. All its key components relied on technologies that only became available in the 1880s. The machine initially confirmed clinical diagnoses of atrial fibrillation and heart block, but came into its own after James Herrick described EKG changes in myocardial infarction in 1918.

The Becton-Dickinson all-metal "Empire," a general utility syringe, was available in sizes from .25 to 8 ounces. It first appeared in the B-D catalog of 1911, where it was offered with a variety of tips for all manner of irrigation (nasal, ear, intra-trachael, intra-venous, urethral, and rectal).

Following the Mauritian physiologist Brown-Séquard’s report on the rejuvenating effects of testicular extract of 1889, physicians began prescribing extracts of the glandular organs of animals to remedy problems associated with the corresponding organ in the human body. Parke, Davis’s “desiccated ovarian residue,” in capsule form, was prescribed in the early twentieth century for conditions associated with ovarian dysfunction, especially menstrual disorders.