The Great Influenza, the Spanish Flu, a viral infection spread by droplets and mouth/nose/hand contact, laid low the residents of dense American cities, and spurred municipal officials to take new initiatives in social distancing.[1] City-wide bans on public gatherings included closing schools, theaters, motion picture houses, dance halls, and – perish the thought – saloons. In major cities, essential businesses that remained open had to comply with new regulations, including staggered opening and closing times to minimize crowd size on streets and in trolleys and subways. Strict new sanitation rules were the order of the day. And yes, eight western cities, not satisfied with preexisting regulations banning public spitting and the use of common cups, or even new regulations requiring the use of cloth handkerchiefs when sneezing or coughing, went the full nine yards: they passed mask-wearing ordinances.

In San Francisco and elsewhere, outdoor barbering and police courts were the new normal.

The idea was a good one; its implementation another matter. In the eight cities in question, those who didn’t make their own masks bought masks sewn from wide-mesh gauze, not the tightly woven medical gauze, four to six layers thick, worn in hospitals and recommended by authorities. Masks made at home from cheesecloth were more porous still. Nor did most bother washing or replacing masks with any great frequency. Still, these factors notwithstanding, the consensus is that masks did slow down the rate of viral transmission, if only as one component of a “layered” strategy of protection.[2] Certainly, as commentators of the time pointed out, masks at least shielded those around the wearer from direct in-your face (literally) droplet infection from sneezes, coughs, and spittle. Masks couldn’t hurt, and we now believe they helped.

Among the eight cities that passed mask-wearing ordinances, San Francisco took the lead. Its mayor, James Rolph, with a nod to the troops packed in transport ships taking them to war-torn France and Belgium, announced that “conscience, patriotism and self-protection demand immediate and rigid compliance” with the mask ordinance. By 1918, masks were entering hospital operating theaters, especially among assisting nurses and interns.[3] But mask-wearing in public by ordinary people was a novelty. In a nation gripped by life-threatening influenza, however, most embraced masks and wore them proudly as emblems of patriotism and public-mindedness. Local Red Cross volunteers lost no time in adding mask preparation to the rolling of bandages and knitting of socks for the boys overseas.

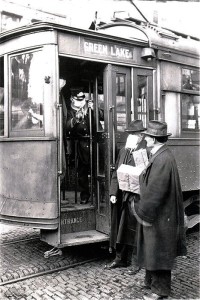

A trolley conductor waves off an unmasked citizen. The image is from Seattle, another city with a mask-wearing ordinance.

But, then as now, not everyone was on board with face masks. Then as now, there were protesters. In San Francisco, they were small in number but large in vocal reach. The difference was that in 1918, cities like San Francisco meant business, with violators of mask laws fined $5 or $10 or imprisoned for 10 days. On the first day the ordinance took effect, 110 were arrested, many with masks dangling around their necks. In mid-November,

San Francisco police arrest “mask slackers,” one of whom has belatedly put on a mask.

following the signing of the Armistice, city officials mistakenly believed the pandemic had passed and rescinded the ordinance. At noon, November 21, at the sound of a city-wide whistle, San Franciscans rose as one and tossed their masks onto sidewalks and streets. In January, however, following a spike in the number of influenza cases, a second mask-wearing ordinance was passed by city supervisors, at which point a small, self-styled Anti-Mask League – the only such League in the nation – emerged on the scene.[4]

A long line of San Franciscans waiting to purchase masks in 1919. A few already have masks in place.

The League did not take matters lying down, nor were they content to point out that masks of questionable quality, improperly used and infrequently replaced, probably did less good than their proponents suggested. Their animus was trained on the very concept of obligatory mask-wearing, whatever its effect on transmission of the unidentified influenza microbe. At a protest of January 27, “freedom and liberty” was their mantra. Throwing public health to the wind, they lumped together mask-wearing, the closing of city schools, and the medical testing of children in school. Making sure sick children did not infect healthy classmates paled alongside the sacrosanctity of parental rights. For the protesters, then as now, parental rights meant freedom to act in the worst interests of the child.

___________________

One wants to say that the Anti-Mask League’s short-lived furor over mask-wearing, school closings, and testing of school children is long behind us. But it is not. In the matter of contagious infectious disease – and expert recommendations to mitigate its impact – what goes around comes around. In the era of Covid-19, when San Francisco mayor London Breed ordered city residents “to wear face coverings in essential businesses, in public facilities, on transit and while performing essential work,” an animated debate on mask-wearing among city officials and the public ensued. A century of advance in the understanding of infectious disease, including the birth and maturation of virology – still counts for little among the current crop of anti-maskers. Their “freedom” to opt for convenience trumps personal safety and the safety of others. Nor does a century of improvements in mask fabrics, construction, comfort, and effectiveness mitigate the adolescent wantonness of this freedom one iota.

“Liberty and freedom.” Just as the Anti-Mask League’s call to arms masked a powerful political undertow, so too with the anti-vaxxers and anti-maskers of the present. Times change; some Americans – a much higher percentage now than in 1918 – do not. Spearheaded by Trumpian extremists mired in fantasies of childlike-freedom from adult responsibility, the “anti” crowd still can’t get its head around the fact that protecting the public’s health – through information, “expert” recommendations and guidelines, and, yes, laws – is the responsibility of government. The responsibility operates through the Commerce Clause of the Constitution, which gives the federal government broad authority to impose health measures to prevent the spread of disease from a foreign country. It operates through the Public Health Service Act, which gives the Secretary of Health and Human Services authority to lead federal health-related responses to public health emergencies. And it operates through the 10th Amendment to the Constitution which grants states broad authority to take action during public health emergencies. Quarantine and restricted movement of those exposed to contagious disease, business restrictions, stay-at-home orders – all are among the “broad public health tools” available to governors.[5]

When a catastrophe, natural or man-made, threatens public health and safety, this responsibility, this prerogative, this Constitutional mandate, may well come down with the force of, well, mandates, which is to say, laws. At such moments in history, we are asked to step up and accept the requisite measure of inconvenience, discomfort, and social and economic restriction because it is intrinsic to the civil liberties that make us a society of citizens, a civil society.

Excepting San Francisco’s anti-masker politicos, it is easier to make allowances for the inexpert mask wearers of 1918 than for anti-masked crusaders today. In 1918, many simply didn’t realize that pulling masks down below the nose negated whatever protection the masks provided. The same is true of the well-meaning but guileless who made small holes in the center of their masks to allow for insertion of a cigarette. It is much harder to excuse the Covid-19 politicos who resisted mask-wearing during the height of the pandemic and now refuse to don face masks in supermarkets and businesses as requested by store managers. The political armor that shields them from prudent good sense, respect for store owners, and the safety of fellow shoppers is of a decidedly baser metal.

The nadir of civil bankruptcy is their virulent hostility toward parents who, in compliance with state, municipal and school board ordinances – or even in their absence – send their children to school donned in face masks. The notion that children wearing protective masks are in some way being abused, tormented, damaged pulls into its orbit all the rage-filled irrationality of the corrosive Trump era. Those who would deny responsible parents the right to act responsibly on behalf of their children are themselves damaged. They bring back to life in a new and chilling context that diagnostic warhorse of asylum psychiatrists (“alienists”) and neurologists of the 19th century: moral insanity.

The topic of child mask-wearing, then and now, requires an essay of its own. By way of prolegomenon, consider the British children pictured below. They are living, walking to school, sitting in their classrooms, and playing outdoors with bulky gas masks in place during the Blitz of London in 1940-1941. How could their parents subject them to these hideous contraptions? Perhaps parents sought to protect their children, to the extent possible, from smoke inhalation and gas attack from German bombing raids. It was a response to a grave national emergency. A grave national emergency. You know, like a global pandemic that to date has brought serious illness to over 46.6 million Americans and claimed over 755,000 American lives.

[1] For an excellent overview of these initiatives, see See Nancy Tomes, “’Destroyer and Teacher’: Managing the Masses During the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic,” Public Health Rep. 125(Suppl 3): 48–62, 2010. My abbreviated account draws on her article.

[2] P. Burnett, “Did Masks Work? — The 1918 Flu Pandemic and the Meaning of Layered Interventions,” Berkeley Library, Oral History Center, University of California, May 23, 2020 (https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/2020/05/23/did-masks-work-the-1918-flu-pandemic-and-the-meaning-of-layered-interventions). Nancy Tomes, “’Destroyer and Teacher’” (n. 1), affirms that the masks were effective enough to slow the rate of transmission.

[3] Although surgical nurses and interns in the U.S. began wearing masks after 1910, surgeons themselves generally refused until the 1920s: “the generation of head physicians rejected them, as well as rubber gloves, in all phases of an operation, as they were considered ‘irritating’.” Christine Matuschek, Friedrich Moll, et al., “The History and Value of Face Masks,” Eur. J. Med. Res., 25: 23, 2020.

[4] My brief summary draws on Brian Dolan, “Unmasking History: Who Was Behind the Anti-Mask League Protests During the 1918 Influenza Epidemic in San Francisco,” Perspective in Medical Humanities, UC Berkeley, May 19, 2020. Another useful account of the mask-wearing ordinance and the reactions to it is the “San Francisco” entry of the The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia, produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing (www.unfluenzaarchive.org/city/city-sanfrancisco.html).

[5] American Bar Association, “Two Centuries of Law Guide Legal Approach to Modern Pandemic,” Around the ABA, April 2020 (https://www.americanbar.org/news/abanews/publications/youraba/2020/youraba-april-2020/law-guides-legal-approach-to-pandem).

Copyright © 2021 by Paul E. Stepansky. All rights reserved. The author kindly requests that educators using his blog essays in courses and seminars let him know via info[at]keynote-books.com.