In the early 19th century, doctors called it angina maligna (gangrenous pharyngitis) or “malignant sore throat.” Then in 1826, the French physician Pierre-Fidele Bretonneau grouped both together as diphtherite. It was a horrible childhood disease in which severe inflammation of the upper respiratory tract gave rise to a false membrane, a “pseudomembrane,” that covered the pharynx, larynx, or both. The massive tissue growth prevented swallowing and blocked airways and often led to rapid death by asphyxiation. It felled adults and children alike, but younger children were especially vulnerable. Looking back on the epidemic that devastated New England in 1735-1736, the lexicographer Noah Webster termed it “literally the plague among children.” It was the epidemic, he added, in which families often lost all, or all but one, of their children.

A century later, diphtheria epidemics continued to target the young, especially those in cities. Diphtheria, not smallpox or cholera, was “the dreaded killer that stalked young children.”[1] It was especially prevalent during the summer months, when children on hot urban streets readily contracted it from one another when they sneezed or coughed or spat. The irony is that a relatively effective treatment for the disease was already in hand.

In 1882, Robert Koch’s assistant, Fredrich Loeffler, published a paper identifying the bacillus – the rod-shaped bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheria first identified by Edwin Klebs – as the cause of diphtheria. German scientists immediately went to work, injecting rats, guinea pigs, and rabbits with live bacilli, and then injecting their blood serum – blood from which cells and clotting factor have been removed – into infected animals to see if the diluted serum could produce a cure. Then they took blood from the “immunized” animal, reduced it to the cell-free blood liquid, and injected it into healthy animals. The latter, to their amazement, did not become ill when injected with diphtheria bacilli. This finding was formalized in the classic paper of Emil von Behring and Shibasaburo Kitsato of 1890, “The Establishment of Diphtheria Immunity and Tetanus Immunity in Animals.” For this, von Behring was awarded the very first Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1901.

Thus the birth of blood serum therapy, precursor of modern vaccines and antibiotics alike. By the early 1890s, Emile Roux and his associates at the Pasteur Institute discovered that infected horses, not the rabbits used by Behring and Kitsato, produced the most potent diphtheria serum of all. Healthy horses injected with a heat-killed broth culture of diphtheria, it was found, could survive repeated inoculations with the live bacilli. The serum, typically referred to as antitoxin, neutralized the highly poisonous substances – the exotoxins – secreted by diphtheria bacteria.

And there was more: horse serum provided a high degree of protection for another mammal, viz., human beings. Among people who received an injection of antitoxin, only one in eight developed symptoms on exposure to diphtheritic individuals. In1895 two American drug companies, H. K. Mulford of Philadelphia and Parke Davis of Chicago, began manufacturing diphtheria antitoxin. To be sure, their drug provided only short-term immunity, but it sufficed to cut the U.S. death rate among hospitalized diphtheria patients in half. This fact, astonishing for its time, fueled the explosion of disease-specific antitoxins, some quite effective, some less so. By 1904 Mulford alone had antitoxin preparations for anthrax, dysentery, meningitis, pneumonia, tetanus, streptococcus infections, and of course diphtheria.

In the era of Covid-19, there are echoes all around of the time when diphtheria permeated the nation’s everyday consciousness. Brilliant scientists, then and now, deploying all the available resources of laboratory science, developed safe and effective cures for a dreaded disease. But more than a century ago, the public’s reception of a new kind of preventive treatment – an injectable horse-derived antitoxin – was unsullied by the resistance of massed anti-vaccinationists whose anti-scientific claims are amplified by that great product of 1980s science, the internet.

To be sure, in the 1890s and early 20th century, fringe Christian sects anticipated our own selectively anti-science Evangelicals. It was sacrilegious, they claimed, to inject the blood product of beasts into human arms, a misgiving that did nothing to assuage their hunger for enormous quantities of beef, pork, and lamb. Obviously, their God had given them a pass to ingest bloody animal flesh. Saving children’s lives with animal blood serum was apparently a different matter.

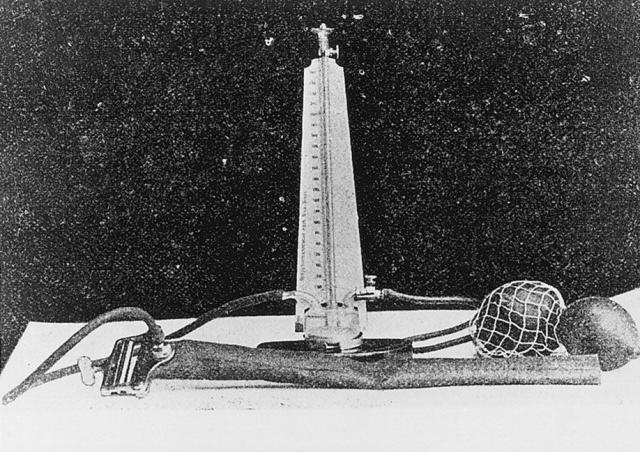

During the summer months, parents lived in anxious expectation of diphtheria every day their children ventured on to city streets. Their fear was warranted and not subject to the denials of self-serving politicians. In 1892, New York City’s Health Department established the first publicly funded bacteriological laboratory in the country, and between 1892 and the summer of 1894, the lab proved its worth by developing a bacteriological test for diagnosing diphtheria. Infected children could now be sent to hospitals and barred from public schools. Medical inspectors, armed with the new lab tests, went into the field to enforce a plethora of health department regulations.

Matters were simplified still further in 1913, when the Viennese pediatrician Bela Schick published the results of experiments demonstrating how to test children for the presence or absence of diphtheria antitoxin without sending their blood to a city lab. Armed with the “Schick test,” public health physicians and nurses could quickly and painlessly determine whether or not a child was immune to diphtheria. For the roughly 30% of New York City school children who had positive reactions, injections of antitoxin could be given on the spot. A manageable program of diphtheria immunization in New York and other cities was now in place.

What about public resistance to the new proto-vaccine? There was very little outside of religious fringe elements. In the tenement districts, residents welcomed public health inspectors into their flats. Intrusion into their lives, it was understood, would keep their children healthy and alive, since it led to aggressive intervention under the aegis of the Health Department.[2] And it was not only the city’s underserved, immigrants among them, who got behind the new initiative. No sooner had Hamann Biggs, head of the city’s bacteriological laboratory, set in motion the lab’s inoculation of horses and preparation of antitoxin, than the New York Herald stepped forward with a fund-raising campaign that revolved around a series of articles dramatizing diphtheria and its “solution” in the form of antitoxin injections. The campaign raised sufficient funds to provide antitoxin for the William Parke Hospital, reserved for patients with communicable diseases, and for the city’s private physicians as well. In short order, the city decided to provide antitoxin to the poor free of charge, and by 1906 the Health Department had 318 diphtheria antitoxin stations administering free shots in all five boroughs.[3][4]

A new campaign by New York City’s Diphtheria Prevention Commission was launched in 1929 and lasted two years. As was the case three decades earlier, big government, represented by state and municipal public health authorities, was not the problem but the solution. To make the point, the Commission’s publicity campaign adopted military metaphors. The enemy was not government telling people what to do; it was the disease itself along with uncooperative physicians and recalcitrant parents. “The very presence of diphtheria,” writes Evelynn Hammonds, “became a synonym for neglect.”[5]

The problem with today’s Covid anti-vaccinationists is that their opposition to vaccination is erected on a foundation of life-preserving vaccination science of which they, their parents, their grandparents, and their children are beneficiaries. They can shrug off the need for Covid-19 vaccination because they have been successfully immunized against the ravages of debilitating childhood diseases. Unlike adults of the late-nineteenth and early-20th centuries, they have not experienced, up close and personal, the devastation wrought summer after summer, year after year, by the diphtheria bacillus. Nor have they lost children to untreated smallpox, scarlet fever, cholera, tetanus, or typhus. Nor, finally, have they, in their own lives, beheld the miraculous transition to a safer world in which children stopped contracting diphtheria en masse, and when those who did contract the disease were usually cured through antitoxin injections.

In the 1890s, the citizens of New York City had it all over the Covid vaccine resisters of today. They realized that the enemy was not public health authorities infringing on their right to keep themselves and their children away from antitoxin-filled syringes. No, the enemy was the microorganism that caused them and especially their children to get sick and sometimes die.

Hail the supremely common sense that led them forward, and pity those among us for whom the scientific sense of the past 150 years has given way to the frontier “medical freedom” of Jacksonian America. Anti-vaccinationist rhetoric, invigorated by the disembodied comaraderie of internet chat groups, does not provide a wall of protection against Covid-19. Delusory thinking is no less delusory because one insists, in concert with others, that infection can be avoided without the assistance of vaccination science. The anti-vaccinationists need to be vaccinated along with the rest of us. A healthy dose of history wouldn’t hurt them either.

[1] Judith Sealander, The Failed Century of the Child: Governing America’s Young in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2003), p. 326.

[2] Evelynn Maxine Hammonds, Childhood’s Deadly Scourge: The Campaign To Control Diphtheria in New York City, 1880-1930 (Baltimore:Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 84-86.

[3] William H. Park, “The History of Diphtheria in New York, City,” Am. J. Dis. Child., 42:1439-1445, 1931.

[4] Marian Moser Jones, Protecting Public Health in New York City: Two Hundred Years of Leadership, 1805-2005 (NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2005), 20.

[5] Hammonds, op cit., p. 206.

Copyright © 2021 by Paul E. Stepansky. All rights reserved. The author kindly requests that educators using his blog essays in courses and seminars let him know via info[at]keynote-books.com.