Malaria (from Italian “bad air”): Infection transmitted to humans by mosquito bites containing single-celled parasites, most commonly Plasmodium (P.) vivax and P. falciparum. Mosquito vector discovered by Ronald Ross of Indian Medical Service in 1897. Symptoms: Initially recurrent (“intermittent”) fever, then constant high fever, violent shakes and shivering, nausea, vomiting. Clinical descriptions as far back as Hippocrates in fifth century B.C. and earlier still in Hindu and Chinese writings. Quinine: Bitter-tasting alkaloid from the bark of cinchona (quina-quina) trees, indigenous to South America and Peru. Used to treat malaria from 1630s through 1920s, when more effective synthetics became available. Isolated from chinchona bark in 1817 by French chemists Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Caventou. There you have it. Now read on.

_______________________

It’s 1779 and the British, commanded by Henry Clinton adopt a southern strategy to occupy the malaria-infested Carolinas. The strategy appears successful, as British troops commanded by Charles Lord Cornwallis capture Charleston on March 29, 1780. But appearances can be deceiving. In reality, the Charleston campaign has left the British force debilitated. Things get worse when Cornwallis marches inland in June, where his force is further ravaged by malarial fever carried by Anopheles mosquitoes and Plasmodium parasites. Lacking quinine, his army simply melts away in the battle to follow. Seeking to preserve what remains of his force, Cornwallis looks to the following winter as a time to recuperate and rebuild. But it is not to be. Clinton sends him to Yorktown, where he occupies a fort between two malarial swamps on the Chesapeake Bay. Washington swoops south and, aided by French troops, besieges the British. The battle is over almost before it has begun. Cornwallis surrenders to Washington, but only after his army has succumbed to malarial bombardment by the vast army of mosquitoes. The Americans have won the Revolutionary War. We owe American independence to Washington’s command, aided, unwittingly, by mosquitoes and malaria.[1]

Almost two centuries later, beginning in the late 1960s, malaria again joins America at war. Now the enemy is communism, and the site is Vietnam. The Republic of Korea (ROK), in support of the war effort, sends over 30,000 soldiers and tens of thousands of civilians to Vietnam. The calculation is plain enough: South Korea seeks to consolidate America’s commitment to its economic growth and military defense in its struggle with North Korean communism after the war. It works, but there is an additional, major benefit: ROK medical care of soldiers and civilians greatly strengthens South Korean capabilities in managing infectious disease and safeguarding public health. Indeed, at war’s end in 1975, ROK is an emergent powerhouse in malaria research and the treatment of parasitic disease. Malaria has again played a part in the service of American war aims.[2]

Winners and losers aside, the battle against malaria is a thread that weaves its way through American military history. When the Civil War erupted in 1861, outbreaks of malaria and its far more lethal cousin, yellow fever, did not discriminate between the forces of North and South. Parasites mowed down combatants with utter impartiality. For many, malarial infection was the enemy that precluded engagement of the enemy. But there were key differences. The North had the U.S. Army Laboratory, comprised of laboratories in Astoria, New York and Philadelphia. In close collaboration with Powers and Weightman, one of only two American pharmaceutical firms then producing quinine, the Army Laboratory provided Union forces with ample purified quinine in standardized doses. Astute Union commanders made sure their troops took quinine prophylactically, with troops summoned to their whiskey-laced quinine ration with the command, “fall in for your quinine.”

Confederate troops were not so lucky. The South lacked chemists able to synthesize quinine from its alkaloid; nor did a Spanish embargo permit the drug’s importation. So the South had to rely on various plants and plant barks, touted by the South Carolina physician and botanist Frances Peyre Porcher as effective quinine substitutes. But Porcher’s quinine substitutes were all ineffective, and the South had to make do with the meager supply of quinine it captured or smuggled. It was a formula for defeat, malarial and otherwise.[3]

Exactly 30 years later, in 1891, Paul Ehrlich announced that the application of a chemical stain, methylene blue, killed malarial microorganisms and could be used to treat malaria.[4] But nothing came of Ehrlich’s breakthrough seven years later in the short-lived Spanish-American War of 1898. Cuba was a haven for infectious microorganisms of all kinds, and, in a campaign of less than four months, malaria mowed down American troops with the same ease it had in the Civil War. Seven times more Americans died from tropical diseases than from Spanish bullets. And malaria topped the list.

As the new century approached, mosquitoes were, in both senses, in the air. In 1900, Walter Reed returned to Cuba to conduct experiments with paid volunteers; they established once and for all that mosquitoes were the disease vector of yellow fever; one could not contract the disease from “fomites,” i.e., the soiled clothing, bedding, and other personal matter of those infected. Two years later, Ronald Ross received his second Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work on the role of mosquitoes in transmission of malaria.[5] But new insight into the mosquito vector of yellow fever and malaria did not mitigate the dismal state of affairs that came with World War I. The American military was no better prepared for the magnitude of malaria outbreaks than during the Civil War. At least 1.5 million doughboys were incapacitated, as malaria spread across Europe from southeast England to the shores of Arabia, and from the Arctic to the Mediterranean. Major epidemics broke out in Macedonia, Palestine, Mesopotamia, Italy, and sub-Saharan Africa.[6]

In the Great War, malaria treatment fell back on quinine, but limited knowledge of malarial parasites compromised its effectiveness. Physicians of the time could not differentiate between the two strains of parasite active in the camps – P. vivax and P. falciparum. As a result, they could not optimize treatment doses according to these somewhat different types of infection. Malarial troops, especially those with falciparum, paid the price. Except for the French, whose vast malaria control plan spared its infantry from infection and led to victory over Bulgarian forces in September 1918, malaria’s contribution to the Great War was what it had always been in war – it was the unexpected adversary of all.

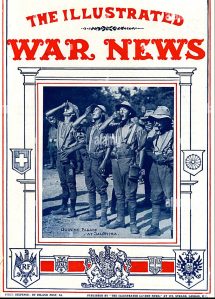

Front cover of “The Illustrated War Times,” showing WWI soldiers, probably Anzacs, taking their daily dose of quine at Salonika, 1916.

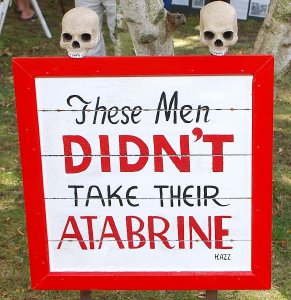

In 1924, the problem that had limited the effectiveness of quinine during the Great War was addressed when the German pharmacologist Wilhelm Roehl, working with Bayer chemist Fritz Schönhöfer, distilled the quinine derivative Plasmoquin, which was far more effective against malaria than quinine.[7] By the time World War II erupted, another antimalarial, Atabrine (quinacrine, mepacrine), synthesized in Germany in1930, was available. It would be the linchpin of the U.S. military’s malaria suppression campaign, as announced by the Surgeon General in Circular Letter No. 56 of December 9, 1941. But the directive had little impact in the early stages of the war. U.S. forces in the South Pacific were devastated by malaria, with as many as 600 malaria cases for every 1,000 GIs.[8] Among American GIs and British Tommies alike, the daily tablets were handed out erratically. Lackluster command and side effects were part of the problem: The drug turned skin yellow and occasionally caused nausea and vomiting. From there, the yellowing skin in particular, GIs leapt to the conclusion that Atabrine would leave them sterile and impotent after the war. How they leapt to this conclusion is anyone’s guess, but there was no medical information available to contradict it.[9]

The anxiety bolstered the shared desire of some GIs to evade military service. A number of them tried to contract malaria in the hope of discharge or transfer – no one was eager to go to Guadalcanal. Those who ended up hospitalized often prolonged their respite by spitting out their Atabrine pills.[10] When it came to taking Atabrine, whether prophylactically or as treatment, members of the Greatest Generation could be, well, less than great.

Sign posted at 363rd Station Hospital in Papua New Guinea in 1942, sternly admonishing U.S. Marines to take their Atabrine.

Malarial parasites are remarkably resilient, with chemically resistant strains emerging time and again. New strains have enabled malaria to find ways of staying ahead of the curve, chemically speaking. During the Korean War (1950-1953), both South Korean and American forces fell to the vivax strain. American cases decreased with the use of chloroquine, but the improvement was offset by a rash of cases back in the U.S., where hypnozoites (dormant malarial parasites) came to life with a vengeance and caused relapses. The use of yet another antimalarial, primaquine, during the latter part of the war brought malaria under better control. But even then, in the final year of the war 3,000 U.S. and 9,000 ROK soldiers fell victim.[11] In Vietnam, malaria reduced the combat strength of some American units by half and felled more troops than bullets. Between 1965 and 1970, the U.S. Army alone reported over 40,000 cases.[12] Malaria control measure were strengthened, yes, but so were the parasites, with the spread of drug-resistant falciparum and the emergence of a new chloroquine-resistant strain.

Malaria’s combatant role in American wars hardly ends with Vietnam. It was a destructive force in 1992, when American troops joined the UN Mission “Operation Restore Hope” in Somalia. Once more, Americans resisted directives to take a daily dose of preventive medicine, now Mefloquine, a vivax antimalarial developed by the Army in 1985. As with Atabrine a half century earlier, false rumors of debilitating side effects led soldiers to stop taking it. And as with Atabrine, malaria relapses knocked out soldiers following their return home, resulting in the largest outbreak of malaria stateside since Vietnam.[13]

In Somalia, as in Vietnam, failure of commanders to educate troops about the importance of “chemoprophylaxis” and to institute “a proper antimalarial regimen” were the primary culprits. As a result, “Use of prophylaxis, including terminal prophylaxis, was not supervised after arrival in the United States, and compliance was reportedly low.[14] It was another failure of malaria control for the U.S. military. A decade later, American combat troops went to Afghanistan, another country with endemic malaria. And there, yet again, “suboptimal compliance with preventive measures” – preventive medication, use of insect repellents, chemically treated tent netting, and so forth – was responsible for “delayed presentations” of malaria after a regiment of U.S. Army Rangers returned home.[15] Plus ca change, plus c’est la même chose.

Surveying American history, it seems that the only thing more certain than malarial parasites during war is the certainty of war itself. Why is this still the case? As to the first question, understanding the importance of “chemoprophylaxis” in the service of personal and public health (including troop strength in the field) has never been a strong suit of Americans. Nor has the importance of preventive measures, whether applying insecticides and tent netting (or wearing face masks) been congenial, historically, to libertarian Americans who prefer freedom in a Hobbesian state of nature to responsible civic behavior. Broad-based public-school education on the public health response to epidemics and pandemics throughout history, culminating in the critical role of preventive measures in containing Coronavirus, might help matters. In the military domain, Major Peter Weima sounded this theme in calling attention to the repeated failure of education in the spread of malaria among American troops in World War II and Somalia. He stressed “the critical contribution of education to the success of clinical preventive efforts. Both in WWII and in Somalia, the failure to address education on multiple levels contributed to ineffective or only partially effective malaria control.” [16] As to why war, in all its malarial ingloriousness, must accompany the human experience, there is no easy answer.

_____________________

[1] Peter McCandless, “Revolutionary fever: Disease and war in the lower South,1776-1783,” Am. Clin. Climat. Assn., 118:225-249, 2007. Matt Ridley provides a popular account in The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge (NY: Harper, 2016).

[2] Mark Harrison & Sung Vin Yim, “War on Two Fronts: The fight against parasites in Korea and Vietnam,” Medical History, 61:401-423, 2017.

[3] Robert D. Hicks, “’The popular dose with doctors’: Quinine and the American Civil War,” Science History Institute, December 6, 2013 (https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/the-popular-dose-with-doctors-quinine-and-the-american-civil-war).

[4] Harry F. Dowling, Fighting Infection: Conquests of the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1977), 93.

[5] Thomas D. Brock, Robert Koch: A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology (Wash, DC: ASM Press, 1998 [1988]), 263.

[6] Bernard J Brabin, “Malaria’s contribution to World War One – The unexpected adversary,” Malaria Journal, 13, 497, 2014; R. Migliani, et al., “History of malaria control in the French armed forces: From Algeria to the Macedonian Front during the First World War” [trans.], Med. Santé Trop, 24:349-61, 2014.

[7] Frank Ryan, The Forgotten Plague: How the Battle Against Tuberculosis was Won and Lost (Boston: Little, Brown,1992), 90-91.

[8] Peter J. Weima, “From Atabrine in World War II to Mefloquine in Somalia: The role of education in preventive medicine,” Mil. Med., 163:635-639, 1998, at 635.

[9] Weima, op. cit., p. 637, quoting Major General, then Captain, Robert Green during the Sicily campaign in August 1943: “ . . . the rumors were rampant, that it made you sterile…. people did turn yellow.”

[10] Ann Elizabeth Pfau, Miss Yourlovin (NY: Columbia Univ. Press, 2008), ch. 5.

[11] R. Jones, et al., “Korean vivax malaria. III. Curative effect and toxicity of Primaquine in doses from 10 to 30 mg daily,” Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 2:977-982, 1953; Joon-Sup Yeom, et al., “Evaluation of Anti-Malarial Effects, J. Korean Med. Sci., 5:707-712, 2005.

[12] B. S. Kakkilaya, “Malaria in Wars and Victims” (malariasite.com).

[13] Weima, op. cit. Cf. M. R. Wallace et al., “Malaria among United States troops in Somalia,” Am. J. Med., 100:49-56, 1996.

[14] CDC, “Malaria among U.S. military personnel returning from Somalia, 1993,” MMWR, 42:524-526, 1993.

[15] Russ S. Kotwal, et al., “An outbreak of malaria in US Army Rangers returning from Afghanistan,” JAMA, 293:212-216, 2005, at 214. Of the 72% of the troops who completed a postdeployment survey, only 31% reported taking both their weekly tablets and continuing with their “terminal chemoprophylaxis” (taking medicine, as directed, after returning home). Contrast this report with one for Italian troops fighting in Afghanistan from 2002-2011. Their medication compliance was measured 86.7% , with no “serious adverse events” reported and no cases of malaria occurring in Afghanistan. Mario S Peragallo, et al., “Risk assessment and prevention of malaria among Italian troops in Afghanistan,” 2002 to 2011,” J. Travel Med., 21:24-32, 2014.

[16] Weima, op. cit., 638.

Copyright © 2022 by Paul E. Stepansky. All rights reserved. The author kindly requests that educators using his blog essays in courses and seminars let him know via info[at]keynote-books.com.