It was the dread disease of the four “D”s: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and death. The symptoms were often severe: deep red rashes, with attendant blistering and skin sloughing on the face, lips, neck, and extremities; copious liquid bowels; and deepening dementia with disorganized speech and a host of neurological symptoms. Death followed up to 40% of the time. The disease was reported in 1771 by the Italian Francisco Frapolini, who observed it among the poor of Lombardy. They called it pelagra – literally “rough skin” in the dialect of northern Italy. Frapolini popularized the term (which later acquired a second “l”), unaware that the Spanish physician Don Gaspar Casal had described the same condition in 1735.

Case reports later identified as pellagra occasionally appeared in American medical journals after the Civil War, but epidemic pellagra only erupted at the dawn of the 20th century. Between 1902 and 1916, it ravaged mill towns in the American South. Reported cases declined during World War I, but resumed their upward climb in 1919, reaching crisis proportions in 1921-1922 and 1927. Nor was pellagra confined to the South. Field workers and day laborers throughout the country, excepting the Pacific Northwest, fell victim. Like yellow fever, a disease initially perceived as a regional problem was elevated to the status of a public health crisis for the nation. But pellagra was especially widespread and horrific in the South.

In the decades following the Civil War, the South struggled to rebuild a shattered economy through a textile industry that revolved around cotton. Pellagra found its mark in the thousands of underpaid mill workers who spun the cotton into yarn and fabric, all the while subsisting on a diet of cheap corn products: cornbread, grits, syrup, brown gravy, fatback, and coffee were the staples. The workers’ meager pay came as credit checks good only at company stores, and what company stores stocked, what the workers could afford to buy, was corn meal. They lacked the time, energy, and means to supplement starvation diets with fresh vegetables grown on their own tiny plots. Pellagra sufferers (“pellagrins”) subsisted on corn; pellagra, it had long been thought, was all about corn. Unsurprisingly, then, it did not stop at the borders of southern mill towns. It also victimized the corn-fed residents of state-run institutions: orphanages, prisons, asylums.

In 1908, when cases of pellagra at southern state hospitals were increasing at an alarming rate, James Woods Babcock, the Harvard-educated superintendent of the South Carolina State Hospital and a pellagra investigator himself, organized the first state-wide pellagra conference.[1] It was held at his own institution, and generated animated dialogue and comraderie among the 90 attendees. It was followed a year later by a second conference, now billed as a national pellagra conference, also at Babcock’s hospital. These conferences underscored both the seriousness of pellagra and the divided opinions about its causes, prevention, and treatment.

At the early conferences, roughly half the attendees, dubbed Zeists (from Zea mays, or maize), were proponents of the centuries-old corn theory of pellagra. What is it about eating corn that causes the disease? “We don’t yet know,” they answered, “but people who contract pellagra subsist on corn products. Ipso facto, corn must lack some nutrient essential to health.” The same claim had been made by Giovanni Marzani in 1810. The Zeists were countered by anti-Zeists under the sway of germ theory. “A deficiency disease based on some mysterious element of animal protein missing in corn? Hardly. There has to be a pathogen at work, though it remains to be discovered.” Perhaps the microorganism was carried by insects, as with yellow fever and malaria. The Italian-born British physician Louis Sambon went a step further. He claimed to have identified the insect in question: it was a black or sand fly of the genus Simulium.

Germ theory gained traction from a different direction. “You say dietary reliance on corn ‘causes’ pellagra? Well, maybe so, but it can’t be a matter of healthy corn. The corn linked to pellagra must be bad corn, i.e., corn contaminated by a protozoon.” Thus the position argued at length by no less than Cesare Lombroso, the pioneer of criminal anthropology. Like Sambon, moreover, he claimed to have the answer: it was, he announced, a fungus, Sporisorium maidis, that made corn moldy and caused pellagra. But many attendees were unpersuaded by the “moldy corn” hypothesis. For them pellagra wasn’t a matter of any type of corn, healthy, moldy, or otherwise. It was an infectious disease pure and simple, and some type of microorganism had to be the culprit. How exactly the microorganism entered the body was a matter for continued theorizing and case reports at conferences to come.

And there matters rested until 1914, when Joseph Goldberger, a public health warrior of Herculean proportions, entered the fray. A Jewish immigrant from Hungary, educated at the Free Academy of New York (later CUNY) and Bellevue Hospital Medical College (later NYU Medical School), Goldberger was a leading light of the Public Health Service’s Hygienic Laboratory. A veteran epidemic fighter, he had earned his stripes battling yellow fever in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and the South; typhoid in Washington, DC; typhus in Mexico City; and dengue fever in Texas.[2] With pellagra now affecting most of the nation, Goldberger was tapped by Surgeon General Rupert Blue to head south and determine once and for all the cause, treatment, and prevention of pellagra.

Joseph Goldberger, M.D.

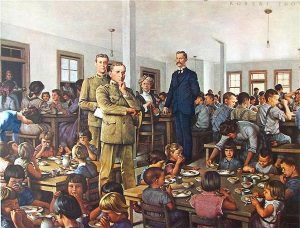

Goldberger was up to the challenge. He took the South by storm and left a storm of anger and resentment in his wake. He began in Mississippi, where reported cases of pellagra would increase from 6,991 in 1913 to 10,954 in 1914. In a series of “feeding experiments” in two orphanages in the spring of 1914, he introduced lean meat, milk, and eggs into the children’s diets; their pellagra vanished. And Goldberger and his staff were quick to make a complementary observation: In all the institutions they investigated, not a single staff member ever contracted pellagra. Why? Well, the staffs of orphanages, prisons, and asylums were quick to take for themselves whatever protein-rich foods came to their institutions. They were not about to make do with the cornbread, corn mush, and fatback given to the hapless residents. And of course their salaries, however modest, enabled them to procure animal protein on the side.

Joseph Goldberger, with his assistant C. H. Waring, in the Baptist Orphanage near Jackson, Mississippi in 1914, in the painting by Robert Thom.

Alright, animal protein cleared up pellagra, but what about residents of state facilities whose diets provide enough protein to protect them from pellagra. Were there any? And, if so, could pellagra be induced in them by restricting them to corn-based diets? Goldberger observed that the only wards of the state who did not contract pellagra were the residents of prison farms. It made sense: They alone received some type of meat at mealtime, along with farm-grown vegetables and buttermilk. In collaboration with Mississippi governor Earl Brewer, Goldberger persuaded 11 residents of Rankin State Prison Farm to restrict themselves to a corn-based diet for six months. At the study’s conclusion, the prisoners would have their sentences commuted, a promise put in writing. The experiment corroborated Goldberger’s previous findings: Six of the 11 prisoners contracted pellagra, and, ill and debilitated, they became free men when the experiment ended in October 1915.

Now southern cotton growers and textile manufacturers rose in arms. Who was this Jewish doctor from the North – a representative of “big government,” no less – to suggest they were crippling and killing mill workers by consigning them to corn-based diets? No, they and their political and medical allies insisted, pellagra had to be an infectious disease spread from worker to worker or transmitted by an insect. To believe otherwise, to suggest the southern workforce was endemically ill and dying because it was denied essential nutrients – this would jeopardize the textile industry and its ability to attract investment dollars outside the region. Goldberger, supremely unfazed by their commitment to science-free profit-making, then undertook the most lurid experiment of all. Joined by his wife Mary and a group of colleagues, he hosted a series of “filth parties” in which the group transfused pellagrin blood into their veins and ingested tablets consisting of the scabs, urine, and feces of pellagra sufferers. Sixteen volunteers at four different sites participated in the experiment, none of whom contracted the disease. Here was definitive proof: pellagra was not an infectious disease communicable person-to-person.[3]

The next battle in Goldberger’s war was a massive survey of over 4,000 residents of textile villages throughout the Piedmont of South Carolina. It began in April 1916 and lasted 2.5 years, with data analysis continuing, in Goldberger’s absence, after America’s entry into the Great War. Drawing on the statistical skills of his PHS colleague, Edgar Sydenstricker, the survey was remarkable for its time and place. Homes were canvassed to determine the incidence of pellagra in relation to sanitation, food accessibly, food supply, family size and composition, and family income. Sydenstricker’s statistical analysis of 747 households with 97 cases of pellagra showed that the proportion of families with pellagra markedly declined as income increased. “Whatever the course that led to an attack of pellagra,” he concluded, “it began with a light pay envelope.” [4]

But Goldberger was not yet ready to retire his suit of armor for the coat of a lab researcher. In September 1919, the PHS reassigned him to Boston, where he joined his old mentor at the Hygienic Laboratory, Milton Rosenau, in exploring influenza with human test subjects. Once the Spanish Flu had subsided, he was able to return to the South, and just in time for a new spike in pellagra rates. By the spring of 1920, wartime prosperity was a thing of the past. Concurrent dips in both cotton prices and tobacco profits led to depressed wages for mill workers and tenant farmers, and a new round of starvation diets led to dramatic increases in pellagra. It was, wrote The New York Times on July 25, 1921, quoting a PHS memo, one of the “worst scourges known to man.”[5]

So Goldberger took up arms again, and in PHS-sponsored gatherings and southern medical conferences, withstood virulent denunciations, often tinged with anti-Semitism. Southern health care officers like South Carolina’s James A. Hayne dismissed the very notion of deficiency disease as “an absurdity.” Hayne angrily refused to believe that pellagra was such a disease because, well, he simply refused to believe it – a dismissal sadly prescient of Covid-deniers who refused to accept the reality of a life-threatening viral pandemic because, well, they simply refused to believe it.[6]

As late as November 1921, at a meeting of the Southern Medical Association, most attendees insisted that pellagra was caused by infection, and that Goldberger’s series of experiments was meaningless. But they were meaningless only to those blinded to any and all meanings that reflected poorly on the South and its ability to feed its working class. Even the slightest chink in the physicians’ self-protective armor would have opened to the epidemiological plausibility of Goldberger’s deficiency model. How could they fail to see that pellagra was a seasonal disease that reappeared every year in late spring or early summer, exactly like endemic scurvy and beriberi, both of which were linked to dietary deficiencies?

Back in the Hygienic Laboratory in Washington, Goldberger donned his lab coat and, beginning in 1922, devised a series of experiments involving both people and dogs. Seeking to find an inexpensive substitute for the meat, milk, and eggs unavailable to the southern poor, he tested a variety of foods and chemicals, one at a time, to see if one or more of them contained the unknown pellagra preventative, now dubbed the “P-P factor.” He was not inattentive to vitamins, but in the early ’20s, there were only vitamins A, B , and C to consider, none of which contained the P-P factor. It was not yet understood that vitamin B was not a single vitamin but a vitamin complex. Only two dietary supplements, the amino acid tryptophan and, surprisingly, brewer’s yeast, were found to have reliably preventive and curative properties.[7]

Brewer’s yeast was inexpensive and widely available in the South. It would soon be put to the test. In June 1927, following two seasons of declining cotton prices, massive flooding of 16,570,627 acres of the lower Mississippi River Valley lowered wages and increased food prices still further. The result was drastic increases in pellagra. So Goldberger, with Sydenstricker at his side, headed South yet again, now hailed on the front page of the Jackson Daily News as a returning hero. After a three-month survey of tenant farmers, whose starvation diet resembled that of the mill workers interviewed in 1916, he arranged for shipment of 12,000 pounds of brewer’s yeast to the hardest hit regions. Three cents’ worth of yeast per day cured most cases of pellagra in six to ten weeks. “Goldberger,” writes Kraut, “had halted an American tragedy.”[8] Beginning with flood relief in 1927, Red Cross and state-sponsored relief efforts following natural disasters followed Goldberger’s lead. Red Cross refugee camps in 1927 and thereafter educated disaster victims about nutrition and pellagra and served meals loaded with P-P factor. On leaving the camps, field workers could take food with them; families with several sick members were sent off with parcels loaded with pellagra preventives.

But the scientific question remained: What exactly did brewer’s yeast, tryptophan, and two other tested products, wheat germ and canned salmon, have in common? By 1928, Goldberger, who had less than a year to live,[9] was convinced it was an undiscovered vitamin, but the discovery would have to await the biochemistry of the 1930s. In the meantime, Goldberger’s empirical demonstration that inexpensive substitutes for animal protein like brewer’s yeast prevented and cured pellagra made a tremendous difference in the lives of the South’s workforce. Many thousands of lives were saved.

___________________

It was only in 1912, when pellagra ripped through the South, that Casimir Funk, a Polish-born American biochemist, like Goldberger a Jew, formulated the vita-amine or vitamine hypothesis to designate organic molecules essential to life but not synthesized by the human body, thereby pointing to the answer Goldberger sought.[10] Funk’s research concerned beriberi, a deficiency disease that causes a meltdown of the central nervous system and cardiac problems to the point of heart failure. In 1919, he determined that it resulted from the depletion of thiamine (vitamin B1). The covering term “vita-amine” reflected his (mistaken) belief that other deficiency diseases – scurvy, rickets, pellagra – would be found to result from the absence of different amines (i.e., nitrogen-containing) molecules.

In the case of pellagra, niacin (aka vitamin B3, aka nicotinic acid/nicotinamide) proved the missing amine, Goldberger’s long sought-after P-P factor. In the course of his research, Funk himself had isolated the niacin molecule, but its discovery as the P-P factor was only made in 1937 by the American biochemist Conrad Elvehjem. The circle of discovery begun with Frapolini’s observations in Lombardy in 1771 was closed between 1937 and 1940, when field studies on pellagrins in northern Italy conducted by the Institute of Biology of the NRC confirmed the curative effect of niacin.[11]

Now, ensnared for 2.5 years by a global pandemic that continues to sicken and kill throughout the world, we are understandably focused on communicable infectious diseases. Reviewing the history of pellagra reminds us that deficiency diseases too have plagued humankind, and in turn brought forth the best that science – deriving here from the collaboration of laboratory researchers, epidemiologists, and public health scientists – has to offer. Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, and Walter Reed are the names that leap to the foreground in considering the triumphs of bacteriology. Casimir Funk, Joseph Goldberger, Edgar Sydenstricker, and Conrad Elvehjem are murky background figures that barely make it onto the radar.

In the developed world, pellagra is long gone, though it remains common in Africa, Indonesia, and China. But the entrenched commercial and political interests that Goldberger and his PHS team battled to the mat are alive and well. Over the course of the Covid pandemic, they have belittled public health experts and bewailed CDC protocols that limit “freedom” to contract the virus and infect others. In 1914, absent Goldberger and his band of Rough Riders, the South would have languished with a seasonally crippled labor force far longer than it did. Mill owners, cotton-growing farmers, and politicians would have shrugged and accepted the death toll as a cost of doing business.

Let us pause, then, and pay homage to Goldberger and his PHS colleagues. They were heroes willing to enter an inhospitable region of the country and, among other things, ingest pills of pellagrin scabs and excreta to prove that pellagra was not a contagious disease. There are echoes of Goldberger in Anthony Fauci, William Schaffner, Ashish Jha, and Leana Wen as they relentlessly fan the embers of scientific awareness among those who resist an inconvenient truth: that scientists, epidemiologists, and public health officers know things about pandemic management that demagogic politicians and unfit judges do not. Indeed, the scientific illiterati appear oblivious to the fact that the health of the public is a bedrock of the social order, that individuals ignore public health directives and recommendations at everyone’s peril. This is no less true now than it was in 1914. Me? I say, “Thank you, Dr. Goldberger. And thank you, Dr. Fauci.”

___________________________

[1] My material on Babcock and the early pellagra conferences at the South Carolina State Hospital come from Charles S. Bryan, Asylum Doctor: James Woods Babcock and the Red Plague of Pellagra (Columbia: Univ. of S C Press, 2014), chs. 3-5.

[2] Alan Kraut, Goldberger’s War: The life and Work of a Public Health Crusader (NY: Hill & Wang, 2004), 7.

[3] To be sure, the “filth parties” did not rule out the possibility of animal or insect transmission of a microorganism. Goldberger’s wife Mary incidentally, was transfused with pellagrin blood but didn’t ingest the filth pills.

[4] Kraut, Goldberger’s War, 164.

[5] Quoted in Kraut, Goldberger’s War, 190.

[6] On Hayne, Goldberger’s loudest and most vitriolic detractor among southern public health officers, see Kraut, pp. 118, 194; Bryan, Asylum Doctor, pp. 170, 223, 232, 239; and Elizabeth Etheridge, The Butterfly Caste: A Social History of Pellagra in the South (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1972), 42, 55, 98-99, 110-111. This is the same James Hayne who in October 1918, in the midst of the Great Pandemic, advised the residents of South Carolina that “The disease itself is not so dangerous: in fact, it is nothing more than what is known as ‘Grippe’” (“Pandemic and Panic: Influenza in 1918 Charleston” [https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/pandemic-and-panic-influenza-1918-charleston#:~:text=Pandemic%20and%20panic%20visited%20Charleston,counter%20a%20major%20health%20crisis]).

[7] The tryptophan experiments were conceived and conducted by Goldberger’s assistant, W. F. Tanner, who, after Goldberger’s return to Washington, continued to work out of the PHS laboratory at Georgia State Sanitarium (Kraut, Goldberger’s War, 203-204, 212-214).

[8] Kraut, Goldberger’s War, 216-222, quoted at 221.

[9] Goldberger died from hypernephroma, a rare form of kidney cancer, on January 17, 1929. Prior to the discovery of niacin, in tribute to Goldberger, scientists referred to the P-P factor as Vitamin G.

[10] The only monographic study of Funk in English, to my knowledge, is Benjamin Harrow, Casimir Funk, Pioneer in Vitamins and Hormones (NY: Dodd, Mead, 1955). There are, however, more recent articles providing brief and accessible overviews of his achievements, e.g., T. H. Juke, “The prevention and conquest of scurvy, beriberi, and pellagra,” Prev. Med., 18:8877-883, 1989; Anna Piro, et al., “Casimir Funk: His discovery of the vitamins and their deficiency disorders,” Ann. Nutr. Metab., 57:85-88, 2010.

[11] Renato Mariani-Costantini & Aldo Mariani-Costantini, “An outline of the history of pellagra in Italy,” J. Anthropol. Sci., 85:163-171, 2007.

Copyright © 2022 by Paul E. Stepansky. All rights reserved. The author kindly requests that educators using his blog essays in courses and seminars let him know via info[at]keynote-books.com.

to protect them from these infectious diseases during the earliest years of life? Is the demographic fact that, owing to vaccination and other public health measures, life expectancy in the U.S. has increased from 47 in 1900 to 77 in 2021 also based on junk data? In my essay,

to protect them from these infectious diseases during the earliest years of life? Is the demographic fact that, owing to vaccination and other public health measures, life expectancy in the U.S. has increased from 47 in 1900 to 77 in 2021 also based on junk data? In my essay,