“saving bits from the wreckage”

[The second of a series of essays about the gallant nurses of World War I commemorating the centennial of America’s entry into the war on April 6, 1917]

The term “blood bath” is always used metaphorically, even in its wartime sense of a bloody massacre in which lives are lost. Often it is used more loosely still, as in the crushing of opponents in sports or business or the purging of employees at a company. “There Could Be a Bloodbath in Sports Media” reads one headline.[1]

For World War I nurses working in casualty clearing stations (CCSs) and field hospitals on the Western Front, however, blood bath could take on a startling literality. Here is Beatrice Hopkinson writing in the fall of 1917 at the height of the third battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), after a general hospital close to her own took a direct hit. She and an orderly began washing sheets and bedding of the bombed-out hospital in a big bath tub: “Soon we seemed to be dabbling in a sea of blood. When the lights were allowed on we looked at one another and we, too, looked as though we had been in a slaughterhouse. Our clothing was blood stained up to our chins; arms and faces too.” Things could be worse still in the operating room, which during major rushes became “a slaughter house,” a blood bath where ambulance drivers, aiding the exhausted nurses, “would seize a mop and pail and swipe up some of the blood from the sloppy floor, or even hold a leg or arm while it was sawn off.”[2]

Hours before the fate of wounded soldiers was decided, it was nurses – not emergency room physicians or combat-trained EMS providers – who triaged incoming wounded, determining which soldiers required emergency treatment for shock; which immediate surgery; which a ward bed to sleep and await treatment; and which quiet removal to the moribund tent to die. Surgeons, who during battles could be operating up to 16 hours a day, had nothing to do with the process. It fell to the trained nurses, the Sisters, to deploy what resources they had to do the sorting, and then to stabilize as quickly as possible those wounded who could be stabilized.

What resources could they summon? How, for example, did they identify wounded soldiers in shock? Absent blood pressure meters and stethoscopes, much less lab studies and scans, they relied on their hands; their hands became instruments of differential diagnosis. Here is Mary Borden’s powerful rendering of her work in the reception hut of a Belgium Casualty Clearing Station:

It was my business to sort out the wounded as they were brought in from the ambulances and to keep them from dying before they got to the operating rooms: it was my business to sort out the nearly dying from the dying. I was there to sort them out and tell how fast life was ebbing in them. Life was leaking away in all of them; but with some there was no hurry, with others it was a case of minutes. . . . My hand could tell of itself one kind of cold from another. They were all half-frozen when they arrived, but the chill of their icy flesh wasn’t the same as the cold inside them when life was almost ebbed away. My hands could instantly tell the difference between the cold of the harsh bitter night and the stealthy cold of death. Then there was another thing, a small fluttering thing. I didn’t think about it or count it. My fingers felt it. I was in a dream, led this way and that by my cute eyes and hands that did many things, and, seemed to know what to do.[3]

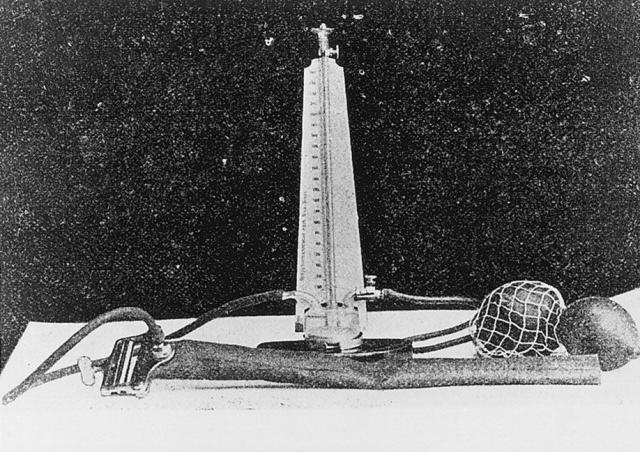

Thus the hands-on method of recognizing what was termed, in the idiom of the time, “wound shock.” For soldiers who arrived off the battlefield in shock, it was nurses who sought to stabilize them by mastering the complicated procedure of pumping saline solution either subcutaneously or intravenously. Why complicated? The patients had to be kept warm, with saline kept at 120 degrees and air kept out of the tubes. And the entire procedure had to be performed aseptically in huts or tents that, depending on the season, could be stifling or freezing.

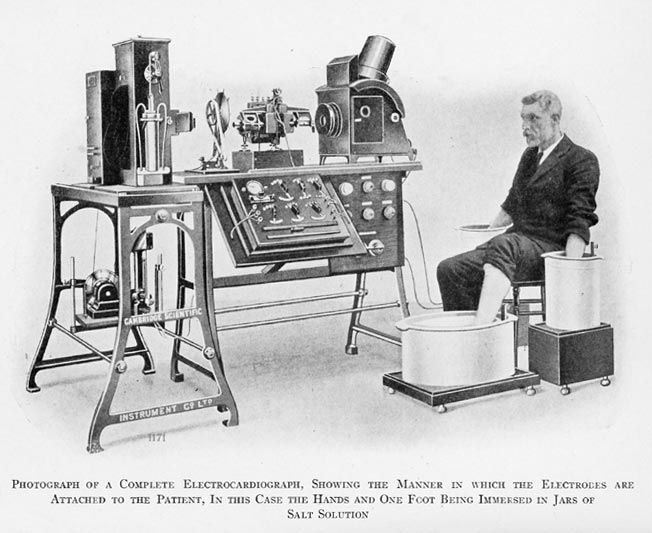

Of course, soldiers off the Front might bleed out even before shock set in. Blood transfusions were not available in WWI until the United States entered the war in 1917, bringing with it transfusion advocates like Boston’s Oswald Robertson, who was invited to British field hospitals to teach transfusion technique and also to show how citrated blood collected from Type O (universal) donors could be stored and shipped. But even in large base hospitals, transfusion remained “a complicated job under the very best of circumstances.”[4] It was never an option in most reception huts of CCSs and field hospitals. So nurses managed hemorrhage with what they had: artery compression, tourniquets, and a variety of constrictive bandages. Skill and reaction time often determined whether soldiers even made it to the surgeons. Following what stabilization the nurses could provide, surgical cases were rushed to the X-ray hut and then to the attached “theatre hut.” There surgeons relied on still other nurses, the “theatre sisters,” to assist them at the operating table.

Nurses’ role as surgical assistants usually continued in the operating theatres of the base hospitals to which survivors were subsequently sent for more extensive repair. In the chaotic overflow of wounded that followed major battles, when as many as seven operating tables might be in continuous use around the clock for two weeks, they really had no choice. “In ten days,” reported Helen Boylston from her front line field hospital in late March, 1917, “we have admitted four thousand eight hundred and fifty-three wounded, sent four thousand to Blighty [England], have done nine hundred and thirty-five operations.” And then, with obvious pride, “– and only twelve patients have died.”[5]

“One doctor and one nurse work at each table,” Julia Stimson wrote her parents from Base Hospital 21 near Rouen several months later,

and you can imagine what surgical work the nurse has to do, no mere handing of instruments and sponges, but sewing and tying up and putting in drains while the doctor takes the next piece of shell out of another place. Than after fourteen hours of this, with freezing feet, to a meal of tea and bread and jam, and off to rest if you can in a wet bell tent in a damp bed without sheets, after a wash with a cupful of water.[6]

Even the auxiliary nurses were co-opted for surgical duty. Kate Norman Derr, the well-off daughter of a former Medical Director in the U.S. Navy, was studying art in France when war broke out in 1914. Resolved to aid the French cause, she volunteered at local hospitals before earning a nursing certificate from the French Red Cross. In September, 1915 she reported to a French field hospital in the Marne Valley where, assigned to the operating ward, she assisted the surgeon in the 25 or more operations performed daily. Horrified by the wounds she encountered, she nonetheless relished her newfound surgical identity. “I think you would sicken with fright if you could see the operations that a poor nurse is called upon to perform,” she wrote her family, referring to “the putting in of drains, the washing of wounds so huge and ghastly as to make one marvel at the endurance that is man’s, the digging about for bits of shrapnel. I assure you that the word responsibility takes a special meaning here.” For Derr, it was the struggle itself, “the sense that one is saving bits from the wreckage,” that shoved aside the sense of being “mastered by the unutterable woe.”[7]

Surgical technique was taught by surgeons who then relegated certain aspects of complex multi-wound operations to the nurses. Shell fragments and shrapnel often lodged in different parts of a soldier’s body, in which case surgeons concentrated on the most penetrative, life threatening wounds while the nurses, forceps in hand, dealt with the more manageable, if far from minor, wounds. The complex wound management that followed surgery, on the other hand, was almost entirely in the nurses’ hands. It began once more in reception huts, where nurses determined which wounds required a surgeon’s attention and which they could handle themselves. For smaller wounds – the term is relative – nursing care became surgical care: nurses irrigated wound beds with saline solution and then debrided the wounds, using sterile probes to locate and remove shrapnel, bone fragments, embedded clothing, and debris. Finally, they dressed the wound with the antiseptics then available – iodine, carbolic acid, hydrogen peroxide, perchloride of mercury, sodium hypochlorite, boracic acid, salicylic acid, chloride of zinc, potassium permaganate, either alone or in combination, in liquid or paste form. Given the plethora of options and toxicity of the more effective antiseptics, choosing the optimal dressing for a particular soldier was no simple matter.

For soldiers with large and infected open wounds – the “gaping wounds” or “horribly bad wounds” or “wounds so huge and ghastly” of which the nurses wrote[8] – it was nurses who mastered the intricacies of the novel and highly effective Carrel-Dakin irrigation method, which saved countless lives and limbs. Here a weak solution of sodium hypochlorite continuously circulated in the wound via a complicated setup in which a glass container fixed at the head of the bed fed tubes with four or five separate nozzles, each connected to another small rubber tube packed into a different part of the wound. The whole affair was held in place with bandages and an adjustable clamp on the main tube to regulate the amount of antiseptic fed into the wound.[9]

Madame Carrel demonstrating the Carrel-Dakin method in a French field hospital in 1917

In cases of compound fracture, nurses themselves usually followed cleaning, irrigation, debridement, and wound dressings with splinting. Back on the ward, with or without a surgeon’s assistance, they began Carrel-Dakin treatment and monitored the fractures, alert, for example, to obstructed circulation. Taking these nursing activities in their totality, Christine Hallett has every reason to conclude that WWI nurses emerged from their European tours as wound care practitioners, adding that, in the rushes that followed major battles, professional boundaries dissolved and their work merged with that of surgeons.[10]

Nurses of the Civil War were no less heroic, if in a different way. They were heroic simply in overcoming the resistance of surgeons and military officers to their presence right off the battlefield, exposed to the naked bodies of wounded men. They were heroic in battling corrupt quartermasters and stewards who withheld supplies and food parcels from the wounded, not to mention racist orderlies who brutalized the wounded, especially African-Americans. And they were heroic in providing comfort care in the tradition of Florence Nightingale, struggling against the system to keep the wounded dry, warm, and adequately fed, “mothering” them with the same compassion as their granddaughters on the Front.

But Civil War nursing lacked the procedural underpinnings of Great War nursing. There was no “scientific nursing” to do because scientific nursing only emerged after the war. The authority they achieved was moral and occasionally administrative. In the latter cases, when nurses became powerful Head Matrons and even founders of their own field hospitals, their authority was typically wrestled from surgeons and officers who never stopped hoping they would pack up and go home. Nurses from elite families – Hannah Ropes, Sophronia Bucklin, Kate Cumming, Clara Barton – sounded off and got results. But the results were moral, not professional, victories. There was no system of triaging for nurses to implement; no protocol in place for cleaning and irrigating infected wounds with saline solution before dressing them with potent antiseptics. Nor were Civil War nurses trained to perform minor surgery in reception tents or to assist surgeons in the operating tent. Very occasionally, a Civil War nurse would rise above the morale-sapping gender prejudice of her camp and find herself alongside an operating surgeon, but she was the heroic exception to the rule.

The heroism of the nurses of WWI has to do with the manner in which they rose to their historical moment, bringing into their operational domain major developments in scientific medicine of the past half century. Consider only the birth of bacteriology; the derivative understanding of antisepsis, asepsis, and sterilization; the development of antiseptics and serum therapy; and major advances in wound management and surgical technique. These developments, conjoined in a combat workplace that relied on collegial staff relationships, enlarged nurses’ responsibilities in a procedural direction. Unlike Civil War nurses, the nurses of World War I initiated medical treatments and performed medical procedures, and they did so without abandoning their traditional obligation to provide care that was calming, comforting, and reassuring. Indeed, with the catastrophic wounding of body and mind made possible by World War I weaponry, the provision of comfort often deepened into supportive psychotherapy and end of life counseling. Psychiatric nursing was born in the CCSs and field hospitals of WWI. The well-trained nurse practitioners of today, empowered in many states to practice medicine (or is it “medicalized” nursing?) with little or no medical supervision, have nothing on their gallant forebears of a century ago.

____________________________

[1] http://thebiglead.com/2015/11/18/fanduel-draftkings-commercials-new-york-attorney-general.

[2] Beatrice Hopkinson, Nursing through Shot & Shell: A Great War Nurse’s Story, ed. Vivien Newman (South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword, 2014), loc 1434; N.A., A War Nurse’s Diary: Sketches from a Belgian Field Hospital (Cornwall, UK: Diggory, 2005), loc 805-820.

[3] Mary Borden, The Forbidden Zone (ed. H. Hutchison (London: Hesperus[1928] 2008), 95-96.

[4] Julia C. Stimson, Finding Themselves: The Letters of an American Army Chief Nurse in a British Hospital in France (NY: Macmillan, 1918), 123.

[5] Helen Dore Boylston, Sister: The War Diary of a Nurse (NY: Washburn, 1927), loc 497.

[6] Stimson, Finding Themselves, 142.

[7] Kate Norman Derr, “Mademoiselle Miss”: Letters from an American Girl Serving with the Rank of Lieutenant in a French Army Hospital at the Front, preface by Richard C. Cabot (Boston: Butterfield, 1916), 33. My great thanks to Alan Kohuth for sending me his original copy of Dere’s letters.

[8] For example, Edith Appleton, A Nurse at the Front: The First World War Diaries, ed. R. Cowen (London: Simon & Schuster UK, 2012), 161, 203; Helen Dore Boylston, Sister: The War Diary of a Nurse (NY: Washburn, 1927), loc 463; Derr, “Mademoiselle Miss,” 33.

[9] The Carrel-Dakin method was devised by Alexis Carrel, a French surgeon, and Henry Dakin, an English chemist, who met in the lab of a field hospital near the forest of Compiegne in France in late 1914. Carrel developed the solution and Dakin devised the apparatus to deliver it. The components of the solution, incidentally, had to be combined in a precise ratio to provide wound sterilization without causing tissue irritation – another procedural feat of the WWI nurses, who prepared and tested every batch of solution from scratch. Their task was greatly simplified in 1917, when Johnson & Johnson of New Brunswick, New Jersey began producing the components in sealed ampoules and vials in the prescribed ratios. Successful use of the method was reported in several articles in the British Medical Journal during the final years of the war. One in particular paid tribute to the Sisters, “whose careful attention to detail largely contributed to the success obtained in the use of the Carrel-Dakin method.” J. S. Dunne, “Notes on Surgical Work in a General Hospital – With Special Reference to the Carrel-Dakin Method of Treatment,” BMJ, 2:283-284, 1918, quoted at 284.

[10] Christine E. Hallett, Containing Trauma: Nursing Work in the First World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), 56-59, 46. Anyone writing about nursing in World War I owes an enormous debt to Hallett, whose two exemplary studies, Containing Trauma (op. cit.) and Veiled Warriors: Allied Nurses of the First World War (NY: OUP, 2014) provide far greater detail of each of the nursing activities I touch on here.

Copyright © 2017 by Paul E. Stepansky. All rights reserved. The author kindly requests that educators using his blog essays in their courses and seminars let him know via info[at]keynote-books.com.