We are pleased to announce the publication of Easing Pain on the Western Front: American Nurses of the Great War and the Birth of Modern Nursing Practice, the book that has grown out of Paul Stepansky’s popular series of blog essays, “Remembering the Nurses of WWI.” It has been lauded as “an important contribution to scholarship on nurses and war” (Patricia D’Antonio, Ph.D.) that is simultaneously “the gripping story of nurses who advanced their profession despite the emotional trauma and physical hardships of combat nursing” (Richard Prior, DNP). The Preface is presented to the readers of “Medicine, Health, and History” in its entirety.

____________________

Dr. Stepansky is the featured author in the Princeton Alumni Weekly

Listen to him discuss Easing Pain on the Western Front with the editor of the Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners in this special JAANP Podcast

____________________

PREFACE

Studies in the history of nursing have their conventions, and this study of American nursing in World War I does not adhere to them. It is not an examination of the total experience of military nurses during the Great war. Excepting only the first chapter, which addresses the American war fever of 1917 and the shared circumstances of the nurses’ enlistment, little attention is paid to aspects of their lives that have engaged other historians. I do not review the nurses’ families of origin, their formative years, or their reasons for entering the nursing profession. Similarly, there is relatively little in these pages of the WWI nurses as women, of their role in the history of the women’s movement, or of their personal relationships, romantic or otherwise, with the men with whom they served.

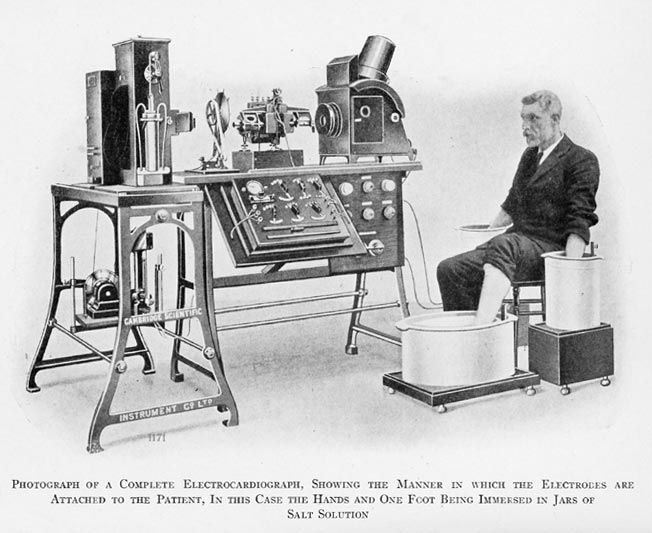

In their place Easing Pain on the Western Front focuses on nursing practice, by which I mean the actual caregiving activities of America’s Great War nurses and their Canadian and British comrades. These activities comprise the role of nurses in diagnosis, in emergency interventions, in medication decisions, in the use of available technologies, and in devising creative solutions to treatment-resistant and otherwise atypical injuries. And it includes, in these several contexts, nurses’ evolving relationship with the physicians alongside whom they worked. Among historians of nursing, Christine Hallett stands out for weaving issues of nursing practice into her excellent accounts of the allied nurses of WWI, with a focus on the nurses of Britain and the British Dominions. Hallett has no counterpart among historians of American nursing, and as a result no effort has been made to gauge the impact of WWI on the trajectory of nurse professionalization in America, both inside and outside the military.

This study begins to address this lacuna from a perspective that stands alongside nursing history. It comes from a historian of ideas who works in the history of American medicine. It is avowedly historicist in nature, grounded in the assumption that nursing practice is not a Platonic universal with a self-evident, objectivist meaning. Rather this type of practice, like all types of practice, is historically determined, with the line between medical treatment and nursing care becoming especially fluid during times of crisis. It is intended to supplement the existing literature on WWI nurses, especially the excellent work of Hallett and other informative studies of British, Canadian, and Australian nurses, respectively. The originality of the work lies in its focus on American nurses, its thematic emphasis on nursing activities, and its argument for the surprisingly modern character of the latter. Close study of nursing practice, especially in the context of specific battlefield injuries, wound infections, and infectious diseases, yields insights that coalesce into a new appreciation of just how much frontline “doctoring” these nurses actually did.

The case for modern nursing practice in WWI is strengthened by comparative historical inquiry that renders the study, I hope, a more general contribution to the history of military nursing and medicine. In each of the chapters to follow, I work into the narrative comparative treatment of WWI nursing with nursing in the American Civil War of 1861-1865, the Spanish-American War of 1898, and/or the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. The gulf that separates Great War nursing from that of wars only two decades earlier, we will see, is wide and deep. In the concluding chapter, I invert the case for modernity by looking forward from America’s Great War nurses to the American nurses who served in World War II and Vietnam. If Great War nurses had little in common with the Civil War nurses who preceded them by a half century, they share a great deal, surprisingly, with their successors in Vietnam a half century later.

The focus on nursing practice, then, far from being restrictive in scope, opens to a wide range of issues – medical, cultural, political, and military. Consider, for example, the very notion of healthcare practice, which is determined by a confluence of factors. Specific theories of disease, rationales for treatment of specific conditions, putative mechanisms of cure, and the grounds for “proving” cure are all central to the historical study of healthcare practice. Female nursing practice, with the bodily intimacies it entails, also implicates considerations of gender – of what, keeping to the time frame of this study, early-twentieth-century female hands might do to male bodies, and what the males who “owned” these bodies might comfortably permit female hands to do. Depending on the historical location of nursing practice, issues of social class, nationality, ethnicity, and race may count for as much or more than gender.

By channeling our gaze onto what nurses of the Great War actually did with wounded, suffering, distraught, and dying soldiers, we learn about the many factors that enter into combat nursing at one moment in modern history. The focus on nursing practice provides a new perspective on the medical advances of the Great War; the role of nurses in making and implementing these advances; the new professional status that accompanied this process; and the American military’s emerging appreciation of trained nurses, indeed of female officers in general. The focus on nursing practice draws a different picture of the evolution of military personnel policy and the changing social mores and political pressures that accompanied this evolution.

The fate of WWI combat nurses’ role back on the homefront in the aftermath of war is a separate story that I address but briefly in the concluding chapter. More work should be done on the relationship between military and civilian nursing practice, especially the fate of combat nurses who return to civilian nursing after wartime service. To keep to the subject matter of this study, the experience of America’s WWI nurses back in civilian hospitals offers an illuminating window into the frustrations and accomplishments of nurses, indeed of professional women in general, in the American workplace in the two decades between the world wars.

For American readers Easing Pain on the Western Front may prove interesting for another reason. Our increasing reliance on nurses to meet the health care challenges of the twenty-first century, especially in the realm of primary care, underscores the relevance of the unsuspectedly modern Great War nurse providers. Indeed, they offer a fascinating point of departure for ongoing debates by nurses, physicians, social scientists, and politicians about the scope of practice of nurse practitioners in relation to physicians. This is because America’s Great War nurses, no less than the nurses of other combatant nations, had to step up during battle “rushes” that overwhelmed their surgeon colleagues. At such times, and in the weeks and months of intensive care that followed, they became autonomous clinical providers, true forebearers of the nurse practitioners and advanced practice nurses of the present day. The fact that their professional leap forward occurred in understaffed casualty clearing stations and field hospitals on the Western front during the second decade of the twentieth century lends salience to their accomplishments.

Notwithstanding the many streams of contingency that flow into nursing practice at a given moment in history, I hasten to point out that I am not a historian of gender and that my comments on gender, not to mention ethnicity and race, are sparing. I invoke them only in the context of specific nursing activities, especially when they were raised by the nurses themselves. The same may be said of the nurses’ personal lives. I ignore neither the emotional toll of combat nursing nor the psychological adaptations to which it gave rise. But here again these issues are addressed primarily in relation to nursing activities, especially the nurses’ perceptions of and reactions to the wounded, ill, and dying they cared for. I leave to others more comprehensive study of the gender-related, racial, and psychological aspects of American military nursing in World War I and other wars, noting only that the scholarship of Darlene Clark Hine, Margaret Sadowski, and Kara Dixon Vuic has begun to mine this rich vein of nursing history to great effect.

The cohort of nurses at the heart of this study is not limited to American nurses. They include Canadian and British nurses as well. In the case of the former, the ground for inclusion is not especially problematic, since many Canadian nurses trained in the United States; indeed, some both trained and worked in the States prior to their wartime service. Ella Mae Bongard, for example, a Canadian from Picton, Ontario, trained at New York Presbyterian Hospital, practiced in New York for two years after graduating in 1915, and then volunteered with the U.S. Army Nursing Corps. She ended up at a British hospital in Étretat, where she served with several of her Presbyterian classmates. The Canadian Alice Isaacson, who served with the Canadian Army Medical Corps, was a naturalized American citizen. Among other members of the Canadian Nurse Corps, Mary Catherine Nichols Gunn trained in Ferrisburg VT and initially worked at Nobel Hospital outside Seattle; Annie Main Gee trained at Minneapolis City Hospital with postgraduate studies at New York Polyclinic; and Eleanor Jane McPhedran trained at New York Hospital School of Nursing and worked in the area for three years after graduating. In all, the training of Canadian nurses and the nursing services they provided were very much in line with American nursing.

In the case of several prominent British nurses cited throughout the work – Kate Luard, Edith Appleton, Dorothea Crewdson – I am arguably on less certain ground. British nurses – veiled and addressed as “Sister” –cannot strictly speaking play a role in American nursing practice during the Great War. I include them nonetheless for several reasons. The fact is that many British nurses, no less than the Canadians, served abroad for the duration of the war; usually their wartime service extended beyond the Armistice of November 1918 by up to a year. The duration of their wartime experience makes their diaries and letters, taken en masse, more revelatory of treatment-related issues than those of their American colleagues, whose term of service was a year or less. The reflections of Canadian and British nurses on nursing practice on the Western front lend illustrative force to the same battlefield injuries, systemic infections, and psychological traumata encountered by the America nurses as well.

Shared nursing practices were reinforced by considerable interchange among the allied nurses. Within months of the outbreak of war, American Red Cross (ARC) nurses, all native born and white per ARC requirements, sailed to Europe to lend a hand. On September 12, 1914, the first 126 departed from New York Harbor on a relief ship officially renamed Red Cross for the duration of the voyage. A second group of 12 nurses joined three surgeons on a separate vessel destined for Serbia. Other nurse contingents followed over the next several months, all part of the American Red Cross’s “Mercy Mission.”

Technically ARC nurses were envoys of a neutral nation, and those in the initial group ended up not only in England and France but in Russia, Austro-Hungary, and Germany as well. In the last the ARC worked in concert with the German Red Cross, and American nurses like Caroline Bauer, stationed in Kosel, Germany in 1915, expressed genuine fondness for the “brave and good” German soldiers under her care. For the majority of nurses, however, pre-1917 service in British and French hospitals, despite some initial tensions with British supervisors, reinforced ideological and emotional bonds and introduced American nurses to the realities of combat nursing on the Western front.

Even after America’s entry into the war in 1917, American nurses were typically assigned on arrival to British or Canadian hospitals, where they continued their tutelage under senior Canadian and British nursing sisters until returning to their units once their hospitals were ready for them. Allowing for occasional exceptions, the same medicines (sometimes with different names) were administered, the same procedures performed, and the same technologies employed by the nurses of the allied nations. To ignore what the Canadian and British nurses have to say about the same issues of nursing practice encountered by the Americans would enervate the study without leading to any refinement of its thesis.

And so, aided by the testimony of Canadian and British nurses, I am secure in my thesis as it pertains to American nursing and the birth of modern nursing practice. That being said, I leave it to scholars more knowledgeable than I about Canadian and British nursing history to validate, amend, or reject the thesis in relation to their respective nations.

Finally, it bears noting that in a work about nursing practice that draws on the recollections of a cohort of American, Canadian, and British nurses, each nurse is very much her own person with a personal story to tell. The memoirs, letters, and diaries that frame this study provide elements of these stories, of how each nurse’s experience interacted with her family history, training, personality, temperament, and capacity for stress management.

In a general way, reactions to the actualities of nursing on the Western front fall along a spectrum of psychological and existential possibilities. At one pole is the affirmation of the combat nursing life provided by Dorothea Crewdson: “I enjoy life here very much indeed. Wonderfully healthy and free.” At the opposite pole are the mordant reflections of the writer Mary Borden, for whom “The nurse is no longer a woman. She is dead already, just as I am – really dead, and past resurrection.” The gamut of reactions, and the richly idiomatic language through which they were expressed, are woven into my narrative at every turn. I am most concerned, however, with the nurses’ transition from one mindset to another, especially the abruptness with which the life-affirming brio of Crewdson gave way to the horror, demoralization, and depersonalization of Borden. The happy excitement and prideful sense of participation in the war effort with which American nurses set out for the front often dissipated shortly after they arrived and saw the human wreckage that would be the locus of their “nursing.”

Signposts of personal transformation, which I gather together as epiphanies, represent my point of departure in chapter 1. But in the chapters that follow, these elements of personal biography are subordinate to my focus on nursing practice through a cohort analysis. Fleshing out the individual stories that undergirded such transformations – the chronicles of strong, often overpowering emotions that took nurses to the point of physical or nervous collapse – is the stuff of biography and falls beyond the task I have set myself. It suffices to recall that nurses, no less than the soldiers they cared for, fell victim to what, in the parlance of the war, was termed “shell shock,” even though medical and military personnel steadfastly refused to pin this label on them. But most of the time the nurses’ descent into the horrific gave rise to adaptive strategies – compartmentalization, dissociation, psychic numbing, black humor – that enabled them to labor on in the service of their soldiers, their “boys.”.

It is with respect to the nurses’ shared ability to bracket their personal stories in the service of a nascent professionalism – a professionalism that segued into medical diagnosis and procedural caregiving far removed from the world of their training and prewar experience – that they reached their full stature. In so doing, they provide an historical example, deeply moving, of the kind of self-overcoming for which we reserve the term “hero.”

_______________

EASING PAIN ON THE WESTERN FRONT

American Nurses of the Great War and the Birth of Modern Nursing Practice

Paul E. Stepansky

McFarland & Co. 978-1476680019 2020 244pp. 19 photos $39.95pbk.

Available now from Amazon

Copyright © 2020 by Paul E. Stepansky. All rights reserved. The author kindly requests that educators using his blog essays in their courses and seminars let him know via info[at]keynote-books.com.