Etymologically, the word “touch” (from the old French touchier) is a semantic cornucopia. In English, of course, common usage embraces dual meanings. We make tactile contact, and we receive emotional contact. The latter meaning is usually passively rendered, in the manner of receiving a gift: we are the beneficiary of someone else’s emotional offering; we are “touched” by a person’s words, gestures, or deeds. The duality extends to the realm of healthcare: as patients, we are touched physically by our physicians (or other providers) but, if we are fortunate, we are also touched emotionally by their kindness, concern, empathy, even love. Here the two kinds of touching are complementary. We are examined (and often experience a measure of contact comfort through the touch) and then comforted by the physician’s sympathetic words; we are touched by the human contact that follows from physical touch.

For nurses, caregiving as touching and being touched has been central to professional identity. The foundations of nursing as a modern “profession” were laid down on the battlefields of Crimea and the American South during the mid-nineteenth century. Crimean and Civil War nurses could not “treat” their patients, but they “touched” them literally and figuratively and, in so doing, individualized their suffering. Their nursing touch was amplified by the caring impulse of mothers: they listened to soldiers’ stories, sought to keep them warm, and especially sought to nourish them, struggling to pry their food parcels away from corrupt medical officers. In the process, they formulated a professional ethos that, in privileging patient care over hospital protocol, was anathema to the professionalism associated with male medical authority.[1]

This alternative, comfort-based vision of professionalism is one reason, among others, that nursing literature is more nuanced than medical literature in exploring the phenomenology and dynamic meanings of touch. It has fallen to nursing researchers to isolate and appraise the tactile components of touch (such as duration, location, intensity, and sensation) and also to differentiate between comforting touch and the touch associated with procedures, i.e., procedural touch.[2] Buttressing the phenomenological viewpoint of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty with recent neurophysiologic research, Catherine Green has recently argued that nurse-patient interaction, with its “heavily tactile component” promotes an experiential oneness: it “plunges the nurse into the patient situation in a direct and immediate way.” To touch, she reminds us, is simultaneously to be touched, so that the nurse’s soothing touch not only promotes deep empathy of the patient’s plight but actually “constitutes” the nurse herself (or himself) in her (or his) very personhood.[3] Other nurse researchers question the intersubjective convergence presumed by Green’s rendering. A survey of hospitalized patients, for example, documents that some patients are ambivalent toward the nurse’s touch, since for them it signifies not only care but also control.[4]

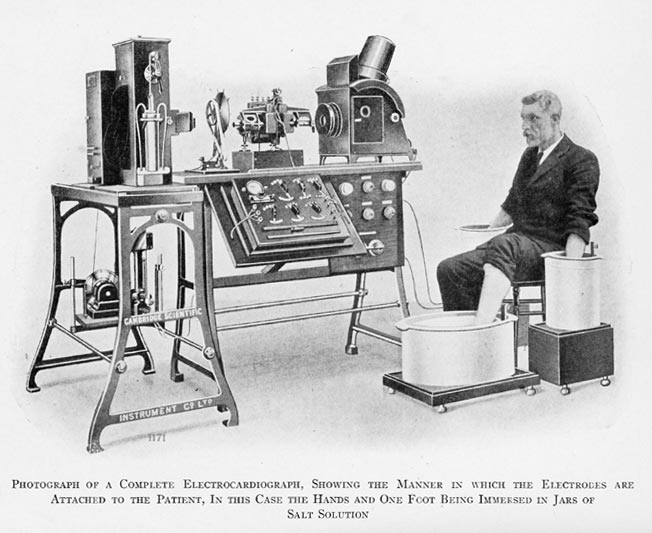

After World War II, the rise of sophisticated monitoring equipment in hospitals pulled American nursing away from hands-on, one-on-one bedside nursing. By the 1960s, hospital nurses, no less than physicians, were “proceduralists” who relied on cardiac and vital function monitors, electronic fetal monitors, and the like for “data” on the patients they “nursed.” They monitored the monitors and, for educators critical of this turn of events, especially psychiatric nurses, had become little more than monitors themselves.

As the historian Margarete Sandelowski has elaborated, this transformation of hospital nursing had both an upside and a downside. It elevated the status of nurses by aligning them with postwar scientific medicine in all its burgeoning technological power. Nurses, the skilled human monitors of the machines, were key players on whom hospitalized patients and their physicians increasingly relied. In the hospital setting, they became “middle managers,”[5] with command authority of their wards. Those nurses with specialized skills – especially those who worked in the newly established intensive care units (ICUs) – were at the top of the nursing pecking order. They were the most medical of the nurses, trained to diagnose and treat life-threating conditions as they arose. As such, they achieved a new collegial status with physicians, the limits of which were all too clear. Yes, physicians relied on nurses (and often learned from them) in the use of the new machines, but they simultaneously demeaned the “practical knowledge” that nurses acquired in the service of advanced technology – as if educating and reassuring patients about the purpose of the machines; maintaining them (and recommending improvements to manufacturers); and utilizing them without medical supervision was something any minimally intelligent person could do.

A special predicament of nursing concerns the impact of monitoring and proceduralism on a profession whose historical raison d’être was hands-on caring, first on the battlefields and then at the bedside. Self-evidently, nurses with advanced procedural skills had to relinquish that most traditional of nursing functions: the laying on of hands. Consider hospital-based nurses who worked full-time as x-ray technicians and microscopists in the early 1900s; who, beginning in the 1930s, monitored polio patients in their iron lungs; who, in the decades following World War II, performed venipuncture as full-time IV therapists; and who, beginning in the 1960s, diagnosed and treated life-threatening conditions in the machine-driven ICUs. Obstetrical nurses who, beginning in the late 1960s, relied on electronic fetal monitors to gauge the progress of labor and who, on detecting “nonreassuring” fetal heart rate patterns, initiated oxygen therapy or terminated oxytocin infusions – these “modern” OB nurses were worlds removed from their pre-1940s forebears, who monitored labor with their hands and eyes in the patient’s own home. Nursing educators grew concerned that, with the growing reliance on electronic metering, nurses were “literally and figuratively ‘losing touch’ with laboring women.”[6]

Nor did the dilemma for nurses end with the pull of machine-age monitoring away from what nursing educators long construed as “true nursing.” It pertained equally to the compensatory efforts to restore the personal touch to nursing in the 1970s and 80s. This is because “true nursing,” as understood by Florence Nightingale and several generations of twentieth-century nursing educators, fell back on gendered touching; to nurse truly and well was to deploy the feminine touch of caring women. If “losing touch” through technology was the price paid for elevated status in the hospital, then restoring touch brought with it the re-gendering (and hence devaluing) of the nurse’s charge: she was, when all was said and done, the womanly helpmate of physicians, those masculine (or masculinized) gatekeepers of scientific medicine in all its curative glory.[7] And yet, in the matter of touching and being touched, gender takes us only so far. What then of male nurses, who insist on the synergy of masculinity, caring, and touch?[8] Is their touch ipso facto deficient in some essential ingredient of true nursing?

As soon as we enter the realm of soothing touch, with its attendant psychological meanings, we encounter a number of binaries. Each pole of a binary is a construct, an example of what the sociologist Max Weber termed an “ideal type.” The question-promoting, if not questionable, nature of these constructs only increases their heuristic value. They give us something to think about. So we have “feminine” and “masculine” touch, as noted above. But we also have the nurse’s touch and, at the other pole, the physician’s touch. In the gendered world of many feminist writers, this binary replicates the gender divide, despite the historical and contemporary reality of women physicians and male nurses.

But the binary extends to women physicians themselves. In their efforts to gain entry to the world of male American medicine, female medical pioneers adopted two radically different strategies. At one pole, we have the touch-comfort-sympathy approach of Elizabeth Blackwell, which assigned women their own feminized domain of practice (child care, nonsurgical obstetrics and gynecology, womanly counseling on matters of sanitation, hygiene, and prevention). At the opposite pole we have the research-oriented, scientific approach of Mary Putnam Jacobi and Marie Zakrezewska, which held that women physicians must be physicians in any and all respects. Only with state-of-the-art training in the medical science (e.g., bacteriology) and treatments (e.g., ovariotomy) of the day, they held, would women docs achieve what they deserved: full parity with medical men. The binary of female physicians as extenders of women’s “natural sphere” versus female physicians as physicians pure and simple runs through the second half of the nineteenth century.[9]

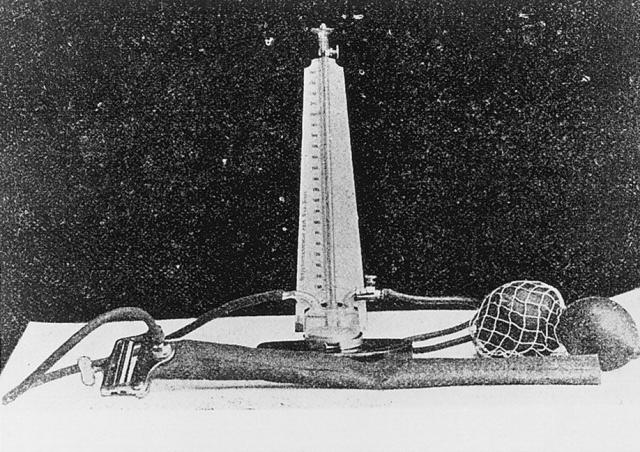

Within medicine, we can perhaps speak of the generalist touch (analogous to the generalist gaze[10]) that can be juxtaposed with the specialist touch. Medical technology, especially tools that amplify the physician’s senses – invite another binary. There is the pole of direct touch and the pole of touch mediated by instrumentation. This binary spans the divide between “direct auscultation,” with the physician’s ear on the patient’s chest, and “mediate auscultation,” with the stethoscope linking (and, for some nineteenth-century patients, coming between) the physician’s ear and the patient’s chest).

Broader than any of the foregoing is the binary that pushes beyond the framework of comfort care per se. Consider it a meta-binary. At one pole is therapeutic touch (TT), whose premise of a preternatural human energy field subject to disturbance and hands-on (or hands-near) remediation is nothing if not a recrudescence of Anton Mesmer’s “vital magnetism” of the late 18th century, with the TT therapist (usually a nurse) taking the role of Mesmer’s magnétiseur.[11] At the opposite pole is transgressive touch. This is the pole of boundary violations typically, though not invariably, associated with touch-free specialties such as psychiatry and psychoanalysis.[12] Transgressive touch signifies inappropriately intimate, usually sexualized, touch that violates the boundaries of professional caring and results in the patient’s dis-comfort and dis-ease, sometimes to the point of leaving the patient traumatized, i.e., “touched in the head.” It also signifies the psychological impairment of the therapist, who, in another etymologically just sense of the term, may be “touched,” given his or her gross inability to maintain a professional treatment relationship.

These binaries invite further scrutiny, less on account of the extremes than of the shades of grayness that span each continuum. Exploration of touch is a messy business, a hands-on business, a psycho-physical business. It may yield important insights but perhaps only fitfully, in the manner of – to invoke a meaning that arose in the early nineteenth century – touch and go.

[1] See J. E. Schultz, “The inhospitable hospital: gender and professionalism in civil war medicine,” Signs, 17:363-392, 1992.

[2] S. J. Weiss, “The language of touch,” Nurs. Res., 28:76-80, 1979; S. J. Weiss, “Psychophysiological effects of caregiver touch on incidence of cardiac dysrhythmia,” Heart and Lung, 15:494-505, 1986; C. A. Estabrooks, “Touch in nursing practice: a historical perspective: 1900-1920,” J. Nursing Hist., 2:33-49, 1987; J. S. Mulaik, et al., “Patients’ perceptions of nurses’ use of touch,” W. J. Nursing Res., 13:306-323, 1991.

[3] C. Green, “Philosophic reflections on the meaning of touch in nurse-patient interactions,” Nurs. Phil., 14:242-253, 2013; quoted at pp. 250-251.

[4] Mulaik, “Patient’s perceptions of nurses’ use of touch,” pp. 317-318.

[5] “Middle managers” is the characterization of the nursing historian Barbara Melosh, in “Doctors, patients, and ‘big nurse’: work and gender in the postwar hospital,” in E. C. Lagemann, ed., Nursing History: New Perspective, New Possibilities (NY: Teachers College Press, 1983), pp. 157-179.

[6] M. Sandelowski, Devices and Desires: Gender, Technology, and American Nursing (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), p. 166.

[7] On the revalorization of the feminine in nursing in the Nursing Theory Movement of the 70s and 80s, see Sandelowski, Devices and Desires, pp. 131-134.

[8] See R. L. Pullen, et al., “Men, caring, & touch,” Men in Nursing, 7:14-17, 2009.

[9] The work of Regina Morantz-Sanchez is especially illuminating of this binary and the major protagonists at the two poles. See R. Morantz, “Feminism, professionalism, and germs: the thought of Mary Putnam Jacobi and Elizabeth Blackwell,” American Quarterly, 34:459-478, 1982, with a slightly revised version of the paper in R. Morantz-Sanchez, Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000 [1985]), pp. 184-202.

[10] I have written about the “generalist gaze” in P. E. Stepansky, The Last Family Doctor: Remembering my Father’s Medicine (Montclair, NJ: Keynote Books, 2011), pp. 62-66, and more recently in P. E. Stepansky, “When generalist values meant general practice: family medicine in post-WWII America” (precirculated paper, American Association for the History of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, May 16-19, 2013).

[11] Therapeutic touch was devised and promulgated by the nursing educator Delores Krieger in publications of the 1970s and 80s, e.g., “Therapeutic touch: the imprimatur of nursing,” Amer. J. Nursing, 75:785-787, 1975; The Therapeutic Touch (NY: Prentice Hall, 1985); and Living the Therapeutic Touch (NY: Dodd, Mead, 1987). I share the viewpoint of Therese Meehan, who sees the technique as a risk-free nursing intervention capable of potentiating a powerful placebo effect (T. C. Meehan, “Therapeutic touch as a nursing intervention,” J. Advanced Nursing, 1:117-125, 1998).

[12] For a fairly recent examination of transgressive touch and its ramifications, see G. O. Gabbard & E. P. Lester, Boundary Violations in Psychoanalysis (Arlington, VA: Amer. Psychiatric Pub., 2002).

Copyright © 2013 by Paul E. Stepansky. All rights reserved.