Looking for a new primary care physician some time back, I received a referral from one of my specialists and called the office. “Doctor’s Office . . .” Thus began my nonconversation with the office receptionist. We never progressed beyond the generic opening, as the receptionist was inarticulate, insensitive, unable to answer basic questions in a direct, professional manner, and dismally unable, after repeated attempts, to pronounce my three-syllable name. When I asked directly whether the doctor was accepting new patients, the receptionist groped for a reply, which eventually took the form of “well, yes, sometimes, under certain circumstances, it all depends, but it would be a long time before you could see her.” When I suggested that the first order of business was to determine whether or not the practice accepted my health insurance, the receptionist, audibly discomfited, replied that someone else would have to call me back to discuss insurance.

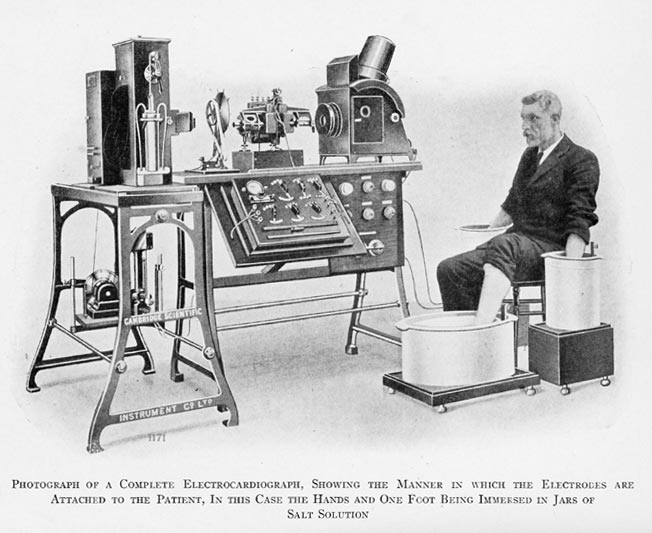

After the receptionist mangled my name four times trying to take down a message for another staff member, with blood pressure rising and anger management kicking in, I decided I had had enough. I injected through her Darwinian approach to name pronunciation – keep trying variants until one of them elicits the adaptive “that’s it!” — that I wanted no part of a practice that made her the point of patient contact and hung up.

Now a brief letter from a former patient to my father, William Stepansky, at the time of his retirement in 1990 after 40 years of family medicine: “One only has to sit in the waiting area for a short while to see the care and respect shown to each and every patient by yourself and your staff.” And this from another former patient on the occasion of his 80th birthday in 2002:

“I heard that you are celebrating a special birthday – your 80th. I wanted to send a note to a very special person to wish you a happy birthday and hope that this finds you and Mrs. Stepansky in good health. We continue to see your son, David, as our primary doctor and are so glad that we stayed with him. He is as nice as you are. I’m sure you know that the entire practice changed. I have to admit that I really miss the days of you in your other office with Shirley [the receptionist] and Connie [the nurse]. I have fond memories of bringing the children in and knowing that they were getting great care and attention.”[1]

Here in microcosm is one aspect of the devolution of American primary care over the past half century. Between my own upset and the nostalgia of my father’s former patient, there is the burgeoning of practice management, which is simply a euphemism for the commercialization of medicine. There is a small literature on the division of labor that follows commercialization, including articles on the role of new-style, techno-savvy office managers with business backgrounds. But there is nothing on the role of phone receptionists save two articles concerned with practice efficiency: one provides the reader with seven “never-fail strategies” for saving time and avoiding phone tag; the other enjoins receptionists to enforce “practice rules” in managing patient demand for appointments.[2] Neither has anything to do, even tangentially, with the psychological role of the receptionist as the modulator of stress and gateway to the practice.

To be sure, the phone receptionist is low man or woman on the staff totem pole. But these people have presumably been trained to do a job. My earlier experience left me befuddled both about what they are trained to do and, equally important, how they are trained to be. If a receptionist cannot tell a prospective patient courteously and professionally (a) whether or not the practice is accepting new patients; (b) whether or not the practice accepts specific insurance plans; and (c) whether or not the doctor grants appointments to prospective patients who wish to introduce themselves, then what exactly are they being trained to do?

There should be a literature on the interpersonal and tension-regulatory aspects of receptionist phone talk. Let me initiate it here. People – especially prospective patients unknown to staff – typically call the doctor with some degree of stress, even trepidation. It is important to reassure the prospective patient that the doctor(s) is a competent and caring provider who has surrounded him- or herself with adjunct staff who share his or her values and welcome patient queries. There is a world of connotative difference between answering the phone with “Doctor’s office,” “Doctor Jones’s office,” “Doctor Jones’s office; Marge speaking,” and “Good morning, Doctor Jones’s office; Marge speaking.” The differences concern the attitudinal and affective signals that are embedded in all interpersonal transactions, even a simple phone query. Each of the aforementioned options has a different interpersonal valence; each, to borrow the terminology of J. L. Austin, the author of speech act theory, has its own perlocutionary effect. Each, that is, makes the recipient of the utterance think and feel and possibly act a certain way apart from the dry content of the communication.[3]

“Doctor’s office” is generic, impersonal, and blatantly commercial; it suggests that the doctor is simply a member of a class of faceless providers whose services comfortably nestle within a business model. “Doctor Jones’s office” at least personalizes the business setting to the extent of identifying a particular doctor who provides the services. Whether she is warm and caring, whether she likes her work, and whether she is happy (or simply willing) to meet and take on new patients – these things remain to be determined. But at least the prospective patient’s intent of seeing one particular doctor (or becoming part of one particular practice) and not merely a recipient of generic doctoring services is acknowledged.

“Doctor Jones’s office; Marge speaking” is a much more humanizing variant. The prospective patient not only receives confirmation that he has sought out one particular doctor (or practice), but also feels that his reaching out has elicited a human response, that his query has landed him in a human community of providers. It is not only that Dr. Jones is one doctor among many, but also that she has among her employees a person comfortable enough in her role to identify herself by name and thereby invite the caller to so identify her – even if he is unknown to her and to the doctor. The two simple words “Marge speaking” establish a bond, which may or may not outlast the initial communication. But for the duration of the phone transaction, at least, “Marge speaking” holds out the promise of what Mary Ainsworth and the legions of attachment researchers who followed her term a “secure attachment.”[4] Prefacing the communication with “Good morning” or “Good afternoon” amplifies the personal connection through simple conviviality, the notion that this receptionist may be a friendly person standing in for a genuinely friendly provider.

Of course, even “Good morning, Marge speaking” is a promissory note; it rewards the prospective patient for taking the first step and encourages him to take a second, which may or may not prove satisfactory. If “Marge” cannot answer reasonable questions (“Is the doctor a board-certified internist” “Is the doctor taking new patients?”) in a courteous, professional manner, the promissory note may come to naught. On the other hand, the more knowledgeable and/or friendly Marge is, the greater the invitation to a preliminary attachment.

Doctors are always free to strengthen the invitation personally, though few have the time or inclination to do so. My internist brother, David Stepansky, told me that when his group practice consolidated offices and replaced the familiar staff that had worked with our father for many years, patient unhappiness at losing the comfortable familiarity of well-liked receptionists was keen and spurred him to action. He prevailed on the office manager to add his personal voicemail to the list of phone options offered to patients who called the practice. Patients unhappy with the new system and personnel could hear his voice and then leave a message that he himself would listen to. Despite the initial concern of the office manager, he continued with this arrangement for many years and never found it taxing. His patients, our father’s former patients, seemed genuinely appreciative of the personal touch and, as a result, never abused the privilege of leaving messages for him. The mere knowledge that they could, if necessary, hear his voice and leave a message for him successfully bridged the transition to a new location and a new staff.

Physicians should impress on their phone receptionists that they not only make appointments but provide new patients with their initial (and perhaps durable) sense of the physician and the staff. Phone receptionists should understand that patients – especially new patients – are not merely consumers buying a service, but individuals who may be, variously, vulnerable, anxious, and/or in pain. There is a gravity, however subliminal, in that first phone call and in those first words offered to the would-be patient. And let there be no doubt: Many patients still cling to the notion that a medical practice – especially a primary care practice – should be, per Winnicott, a “holding environment,” if only in the minimalist sense that the leap to scheduling an appointment will land one in good and even caring hands.

[1] The first quoted passage is reprinted in P. E. Stepansky, The Last Family Doctor: Remembering My Father’s Medicine (Keynote, 2011), p. 123. The second passage is not in the book and is among my father’s personal effects.

[2] L. Macmillan & M. Pringle, “Practice managers and practice management,” BMJ, 304:1672-1674, 1992; L . S. Hill, “Telephone techniques and etiquette: a medical practice staff training tool,” J. Med. Pract. Manage., 3:166-170, 2007; M. Gallagher, et al., “Managing patient demand: a qualitative study of appointment making in general practice,” Brit. J. Gen. Pract., 51:280-285, 2001.

[3] See J. L. Austin, How To Do Things with Words (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962) and the work of his student, J. R. Searle, Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970).

[4] Ainsworth’s typology of mother-infant attachment states grew out of her observational research on mother-infant pairs in Uganda, gathered in her Infancy in Uganda (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1967). On the nature of secure attachments, see especially J. Bowlby, A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development(New York: Basic Books, 1988) and I. Bretherton, “The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth,” Develop. Psychol., 28:759-775, 1992.

Copyright © 2012 by Paul E. Stepansky. All rights reserved.